NORTH WARD HISTORIC

RESOURCE SURVEY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

SURVEY AREAS/COMMUNITIES:

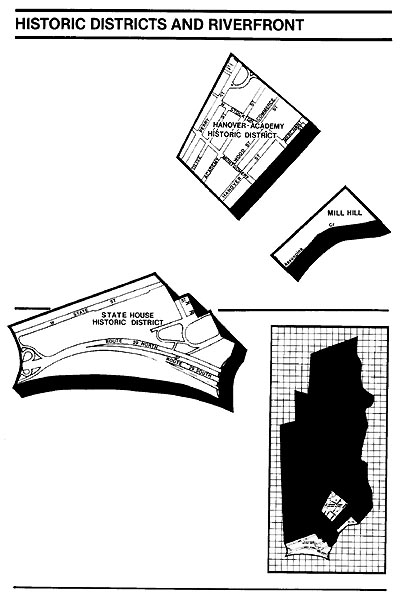

HISTORIC DISTRICTS & WATERFRONT

(click on this North Ward map for a larger image)

INTRODUCTION

Preservation,

the alternative to the destruction and disfiguration of our community’s older

structures, provides the key to our city’s successful revitalization. Looking

closely at the buildings that surround us, we see their irreplaceable richness

and variety. These qualities give older structures their value and significance.

Throughout history, the character of buildings has

changed, reflecting the taste, technology and culture of their times. As our

lifestyle changes, these physical mementos of bygone eras acquire added importance

making them worthy of preservation.

Preservation, therefore, does not only apply to a few

isolated monuments, but to an increasingly broad spectrum of buildings that

constitute our environment. We must value our more recent heritage and insure

its preservation for future generations.

Preservation addresses a variety of other factors.

Is the building representative of the period in which it was constructed?

Is it in some way especially unique or advanced? Does it contain any ornamentation

or detailed craftsmanship that would be irreplaceable today? Does the individual

building play a supportive role contributing to the streetscape? Preservation

used as a planning strategy can help define groups of significant buildings

or districts, such as Mill Hill and the State House Historic Districts; the

identified areas can form the basis of a neighborhood revitalization effort.

The survey is the foundation of ongoing preservation

activity. It identifies and examines buildings of architectural merit worthy

of preservation. This booklet is the result of the city’s survey of the North

Ward. Combining traditional history with the physical artifacts of that history,

the booklet studies each of the North Ward’s historical communities providing

a background narrative accompanied by a listing of significant buildings.

A more detailed description and statement of significance for these structures

is in the companion handbooks.

HISTORIC DISTRICTS AND RIVERFRONT

The

existing Academy-Hanover Historic District, and the parts of the State House

and Mill Hill Historic Districts which lie in the North Ward have already

been surveyed and have received only cursory consideration in this survey.

Land along the Delaware River south of the State House Historic District has

been considered independently of any other area.

The Academy-Hanover Historic District consists of one

of Trenton’s oldest residential neighborhoods. It includes the east-west streets

of East Hanover, laid out about 1735, Academy, laid out about 1774, and Perry,

laid out in 1814. Although development began as early as the mid-eighteenth

century, growth was slow until the opening of Perry Street - which quickly

became more populous than the older streets. Perry Street served as the important

link between Warren Street and the Millham Road

and acquired a partial commercial character. East Hanover Street, adjacent

to the downtown, became popular for professional offices. An industrial zone

developed at the eastern edge of the neighborhood along the canal. For the

most part, however, the area has always been residential. Great growth in

population and housing occurred between 1850 and 1880 when nearly all lots

were developed.

Notable institutions have been founded and have flourished

within the district boundaries. The Trenton Academy preparatory school (1782-1884)

and the Joseph Wood Public School (1857-1932) were two of Trenton’s premier

educational institutions. They have been replaced by the building of the Trenton

Free Public Library. Trenton’s earliest “church,” the Friend’s Meeting House

on East Hanover Street still stands (1739 with alterations). The First Methodist,

Central Baptist and Trinity Episcopal Churches were at one time located in

the neighborhood.

Mid-nineteenth century Perry Street was a focus of

Trenton’s small black community. Mount Zion A.M.E. Church, founded in 1816

on the present site, is Trenton’s oldest black organization. A sizeable Jewish

community was active in the area.

The neighborhood retains its original character with

residential streets lined largely with brick row houses - interrupted by a

few more high-style homes, small office and commercial buildings, and institutional

structures. Few of the buildings are notable solely on their own merits. But

the totality constitutes a representative mixed-class neighborhood of the

nineteenth century. Although in need of revitalization, the Academy-Hanover

Historic District remains one of Trenton’s oldest and most ethnically and

physically diverse neighborhoods.

The State House Historic District includes structures

on Willow Street and on West State Street, from Willow Street extending a

short distance into the West Ward beyond Calhoun Street. The first ironworks

in New Jersey (established by Benjamin Yard), and the Old Barracks and Old

Masonic Hall were located in the area before the end of the eighteenth century.

The construction of the New Jersey State House on an extension of Second Street

(State) in 1791 ensured further development. South Willow Street acquired

a cluster of institutional buildings, while West State Street developed toward

the west throughout the nineteenth century as Trenton’s most fashionable residential

street.

Early homes were modest; but this district is a rare

instance of residential redevelopment in Trenton as the original houses were

often replaced by more pretentious structures. In its present manifestation,

West State Street contains worthy buildings representing nearly every significant

nineteenth century architectural style. The more outstanding houses are the

Greek Revival Joseph Wood House, the Italianate Contemporary Club, and the

Romanesque Roebling Row. These are all closely set townhouse-type structures.

(A series of freestanding deeply set back mansions formerly stood on the south

side of the street. These have all been demolished.)

The State House, though repeatedly altered and expanded,

is the country’s second oldest state capital still in use, dominating the

street with its curious nearly freestanding golden dome.

At the corner of West State Street and South Willow

Street is the Kelsey Building, an individualistic Italianate essay originally

designed for the School of Industrial Arts by Cass Gilbert. It features excellent

terra cotta tile and metal work and a tile roof. The monumental Beaux Arts

1929 Masonic Temple and War Memorial Building face South Willow Street in

counterpoint to the eighteenth century Old Barracks and Old Masonic Hall.

Land between the State House Historic District and

the Delaware River lies apart from North Ward neighborhoods and historic districts.

In the eighteenth century, this land was traversed by the stream known as

Petit’s Run, becoming Trenton’s first industrial

district with establishments such as Stacy Pott’s

steelworks. The opening of the “Sanhican Creek”

water power raceway parallel to the river spawned further industrial growth.

Industry remained in the area well into the twentieth century, as did the

swampy riverfront lowlands which comprised much of the remaining acreage.

In 1911, efforts to develop the area as a riverfront

park began with the construction of a retaining wall and landscaping. The

eventual result was Mahlon Stacy Park. The park,

with its trees, paths, and concert bandshell became

popular with Trentonians as a pleasure ground for

strolling and entertainment. In recent years, the row of mansions which faced

West State Street has been replaced by the New Jersey State Cultural Center.

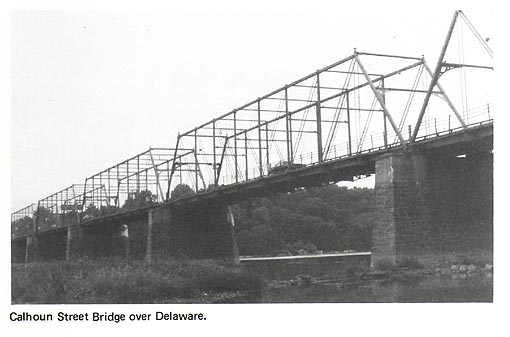

At the very southwestern edge of the North Ward, the

Calhoun Street Bridge crosses the Delaware River. Erected in 1885 by the Trenton

City Bridge Company, the Calhoun Street bridge is a rare surviving example

of a long Pratt truss bridge. It is listed on the National Register of Historic

Places. With the exception of Roebling’s Lackawaxen Aqueduct, it is the oldest bridge spanning the

Delaware River.

A small portion of the Mill Hill Historic District

lies in the North Ward, while the remainder is in the South Ward. The area

in question lies just north of the Assunpink Creek between South Broad and

South Stockton Streets. Mahlon Stacy’s original

mill was in the vicinity, and the Second Battle of Trenton was fought over

the Broad Street bridge over the Assunpink. A narrow seam between the Downtown

and the Mill Hill Mercer-Jackson Streets neighborhood, the area has no particularly

significant community identity of its own.

This small strip along Front Street is now divided

from the Downtown by parking lots and linked to Mill Hill by the park along

the creek. It includes noteworthy structures such as the oft-moved eighteenth

century Douglas House, the former Lutheran Church of Our Saviour,

presently adaptively reused as the Mill Hill Community Playhouse, distinctive

townhouses of a number of eclectic stylistic variations, contemporary housing

for the elderly, and a monumental statue of George Washington.

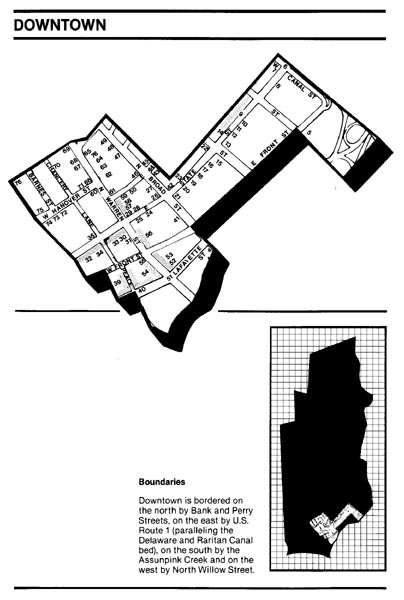

DOWNTOWN

History &

Development

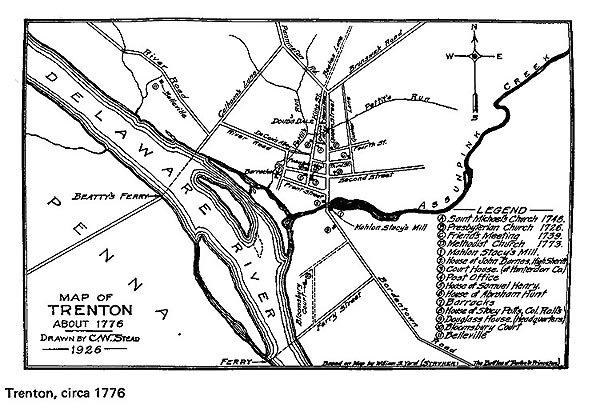

All

of Trenton was contained in the

downtown area during the eighteenth century. Open land, farms, and woodland

surrounded this compact village. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the history

and development of Downtown was nearly synonymous with the history and development

of Trenton itself.

In

1748, Peter Kalm, a visitor from Sweden, described

the town as follows:

“October the 28th. Trenton is a long narrow town

. . . It has small churches. The houses are partly built of stone, though

most of them are made of wood planks, commonly two stories high, together

with a cellar below the building, and a kitchen under ground, close to the

cellar. These houses stand at a moderate distance from one another. They are

commonly built so that the street passes along one side of the houses, while

gardens with different dimensions bound the other side . . . Our landlord

told us that twenty-two years ago, when he settled here, there was hardly

more than one house; but from that time Trenton has increased so much that

there are at present near a hundred houses.” 1

As Kalm’s diary indicates,

houses comprised the largest share of the building stock. A small enclave

of simplified Federal and Italianate row houses along Peace Street and Lafayette

Street (#39, #40) still retains a residential character. In most of the downtown

area, however, houses were gradually replaced or converted to non-residential

uses, especially as the ground floors gave way to storefronts. The Federal

and Italianate structures lining Warren Street between Front and Lafayette

Streets (#52, #54) are perhaps most representative of this phenomenon. A few

blocks north, the imposing Centennial Row (#48) on North Broad Street is a

prominent late nineteenth century example of more elaborate Italianate residences.

2

Change has steadily continued, and downtown is the

only section of Trenton where it is not uncommon for a given parcel of land

to have supported more than one generation of structures. Until the mid-nineteenth

century, the downtown remained a mix of residential, commercial, institutional

and some industrial uses. Trenton’s buildings have evolved through the years

reflecting the dynamic nature of the downtown’s social, institutional and

commercial life.

Transportation

Transportation

was one of the single most powerful factors giving direction to the City’s

growth. In the early eighteenth century, Trenton served as an important transportation

center with stage service between Trenton and Philadelphia; service to New

Brunswick and New York followed shortly thereafter. Initially, the stage route

ran directly through town on Queen Street, which later became known as Greene

Street and finally Broad Street. By the late eighteenth century, however,

the route had been altered; drivers turned west at Second Street (State Street)

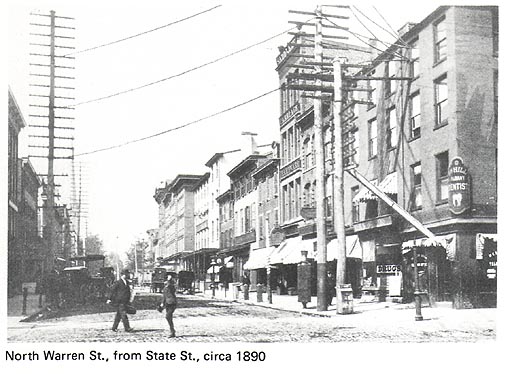

and then north on King Street (Warren Street) 3

This new route established a new axis of urban development marked by taverns

and inns, churches, the county courthouse, leading businesses, and the town

street market. 4 However, by the mid-nineteenth

century, Queen Street (Broad Street) had begun to surpass King Street (Warren

Street) in importance, becoming the City’s principal street. At the turn of

the century, State Street became the City’s main business street. As transportation

developed technologically, it had a dramatic influence on the City’s growth.

The development of canals, railroads and street-cars, and the dispersal of

industry and population that resulted, transformed downtown almost entirely

into a commercial and institutional center.

Social Life

Prior

to this more sophisticated, urban life-style, the village was a major crossroads

with many taverns and inns catering to travelers and residents. Village life

revolved around taverns as well as the market place, churches, fraternal organizations,

and theater.

The taverns and inns offered food, drink, and fellowship,

providing ideal meeting places. In 1784, at the French Arms Tavern at King

and Second Streets, Congress met to deliberate naming Trenton the capital

city of the nation. Trenton served only briefly as the presidential and cabinet

seat for John Adams. The French Arms and later the Sign of the Golden Swan

were each, for a time, Trenton’s most suitable place for large gatherings.

Other popularly frequented institutions included the Rising Sun, the Indian

King, the Phoenix Hotel, and the City Hotel, all on King Street (Warren Street).

Today, the Trenton House (#59), the American Hotel (#60), and the Sign of

the Golden Swan (#55) remain standing. A Federal style building originally

built probably as a residence in 1815 served as the Golden Swan Tavern between

1826 and 1855. It then served as newspaper offices of the True American, predecessor to the Trenton Times, and is presently a custom tailor shop. At the corner

of North Warren and Hanover Streets, the American Hotel, dating from 1847,

has accommodated such luminaries as President James K. Polk and Daniel Webster.

One of the country’s most historic hotels, the Trenton House stands across

the street. The Tremont House (#7), built in 1847 at the corner of East State

and Canal Streets, served travelers on the Camden and Amboy Railroad.

For

Trentonians, day to day activity revolved around

the street market place. Complete with whipping post, stocks and town pump,

it was a favorite place for meeting friends and hearing the latest gossip.

An early nineteenth century observer wrote in the State

Gazette:

“A Saturday night in Trenton seems to be particularly appropriate to promenading

. . . seven hundred and fourteen persons passed the corner of Warren and Second

(State) from 8 o’clock to 10 last Saturday night. Some with a lady on each

arm; others admirably paired off, and hundreds were promenading single handed

and alone. The industrious mechanic, with his neatly dressed wife - on one

arm, and a capacious market basket on the other - making his purchases . .

. .” 5

Besides good conversation and comraderie,

the market stalls offered a wide choice of provisions. Commercial activity

began in shops like that of gunsmith John Fitch,

who later was to launch the first successful steamboat. His shop was located

on King Street (Warren Street), as was the general provisions store of the

leading merchant, Abraham Hunt. 6

The churches, likewise, provided fellowship and served

as meeting places. Prominent churches included St. Michael’s Episcopal (#65)

“The English Church” 1784, the First Presbyterian Church (#23) 1728, the First

Methodist (#41), St. Mary’s Cathedral (#69), and St. Francis Roman Catholic

Church (#36). While these congregations still have prominent buildings in

the downtown, only St. Michael’s remains in its original building, although

in a much altered form. St. Michael’s Church on North Warren Street was originally

constructed in 1748, and subsequently rebuilt a number of times. 7

The present facade, dating from 1851, is a fine and rare example of a castellated Gothic Revival design. The Classical Revival First

Presbyterian Church on East State Street (#23) dates from 1841. Both churches

have flanking churchyards with gravestones dating from the eighteenth century.

The daughter of Joseph Bonaparte is buried at St.

Michael’s; Colonel Rall and a handful of Hessians, and the first three mayors of Trenton are buried

at the First Presbyterian. The brownstone former Third Presbyterian Church

on North Warren Street was built in 1850 (#67); the St. Francis Roman Catholic

Church building now sheathed with permastone, dates

from 1841 (#30); the Romanesque First Methodist Church, a tall tile-faced

building with Gothic detailing, dates from 1894 (#41).

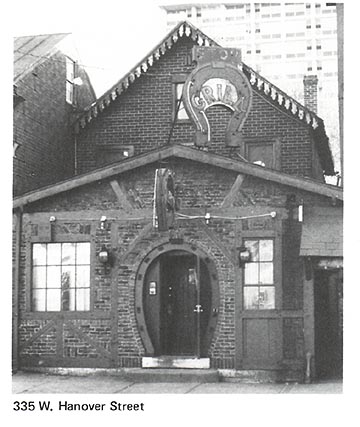

Fraternal organizations also built prominent structures and contributed much to community life. The Masons, in particular, played a distinguished role in Trenton social and political life. Organizations such as the Elks (#62) and the Eagles (#65) established downtown lodges. The Elks Lodge is a romantic extravaganza of brick and stone with geometric tile inlays.

Theaters also emerged as a new focus of social life

and entertainment during this period. The first large theatrical hall, the

Taylor Opera House, opened in 1867; it became known for its vaudeville performances.

Other halls followed, leading to extravagant movie “palaces” such as “The

Trent” and “The Lincoln.”

Along

with social activities, a number of both private and public institutions emerged

as an integral part of downtown Trenton.

In 1719, Trenton became the county seat of Hunterdon County. Mercer County was created out of Hunterdon and a portion of Burlington Counties. The town’s

primary institutional building was the Hunterdon

County Courthouse and Jail on King Street (Warren Street), built in 1730 (#56).

In 1753 the townspeople saw construction completed on the first post office,

also on King Street (Warren Street), and a school on Second Street (State

Street).

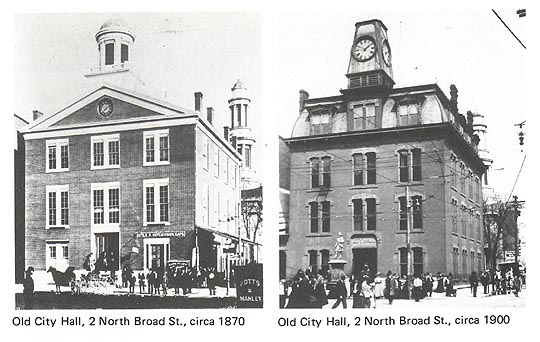

Trenton’s first City Hall (#42) built in 1836, holds

a particular interest because of its metamorphosis. 8

Originally designed in the Federal Style, a French Second Empire mansard

roof and clock tower as well as new fenestration and brick cladding were the

results of a late nineteenth century remodeling. In its present form, the

building stands without its tower while the upper floors’ fenestration has

given way to tall glass block panels. The first floor has been totally rebuilt.

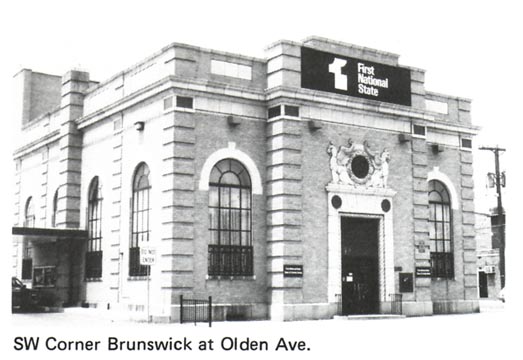

During the late nineteenth century downtown Trenton also became a banking center. In fact, banks now assert the most commanding physical presence in the area, characterized by the dignified, stolid presence of a series of Classical/Beaux Arts structures. This academic style provided an appropriate iconography for banks, the financial pillars of the community. The greatest flourish of this style appears in the Trenton Savings Fund Society (#19) at 123 East State Street.

The monumental New Jersey National Bank building (#30),

originally the First Mechanics National Bank, is located at the corner of

West State and South Warren Streets. A prime example of downtown’s continuous

evolution, this structure is on the site of three generations of bank buildings.

9 Originally this corner was the site of

the French Arms Tavern.

Neo-Classically detailed office towers above the

main banking halls represent another type of bank structure. These office

towers, downtown’s tallest and most ambitious buildings, are often topped

by massive advertising signs (#15, #35).

Downtown Today

Today,

the physical character of eighteenth and nineteenth century downtown is most

evident and best preserved on Warren Street. South Warren Street (#30, #52,

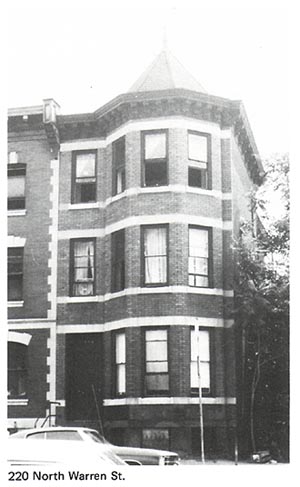

#54, #55, #56) and North Warren Street between State and Bank-Perry Streets

(#29, #57 through #69) boast architecturally varied streetscapes including

churches (#65, #67, #69), former inns and hotels (#55, #59, #60), noteworthy

Italianate commercial buildings (#30, #52, #54, #57, #63,

#64, #66) and Trenton’s most significant pressed metal facade at the True

American Building (#58).

The mid-nineteenth century shift of preeminence from

Warren Street to Broad Street is marked by buildings such as the large four

story Italianate commercial structure bearing an

1856 datestone (#43).

Today, downtown commercial activity focuses around

a two block pedestrian mall located on East State Street flanking Broad Street.

The Commons contains a number of notable architectural compositions. At 9

East State Street (#25) a Victorian pressed metal ornamental facade dated

1896 is dominated by a more recent, yet significant porcelain enamel and neon

Flagg Brothers Sign.

Across

the street the McDonald’s facade at 12-14 (#28), combines Art Deco and Classical

motifs forming a uniquely modern composition. Once a Horn and Hardart this building has housed two generations of fast food

establishments. The Commons also includes a simple Art Deco Woolworth’s (#20)

as well as the quietly modernistic Kresge Store

(#21).

Although the street markets, the town pump, and the

whipping posts have disappeared, the Commons possesses a special character

all its own and provides the public with numerous shops.

1 Turk, “Trenton, New Jersey in the Nineteenth Century;”

p. 60.

2 Centennial Row was erected by the Rev. Anthony Smith,

a priest at St. Mary’s Cathedral. See Walker, et. al., A History

of Trenton, pp. 324-325.

3 Turk, “Trenton, New Jersey in the Nineteenth Century;”

p. 44.

4 Harry J. Podmore “The Historic

Five Points in Trenton;” The Silent

Worker, Vol. 33, no. 2, November, 1924, p. 55.

5 Harry J. Podmore, Trenton Old and New (Trenton: Trenton Tercentenary

Commission, 1964), p. 84.

6 Walker, et. al., A History of Trenton, pp. 107-108.

7 Hamilton A. Schuyler, A History of St. Michael’s Church, (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1926).

8 Podmore, Trenton Old and New, pp. 94-101.

9 Podmore, Trenton Old and New, pp. 59-64.

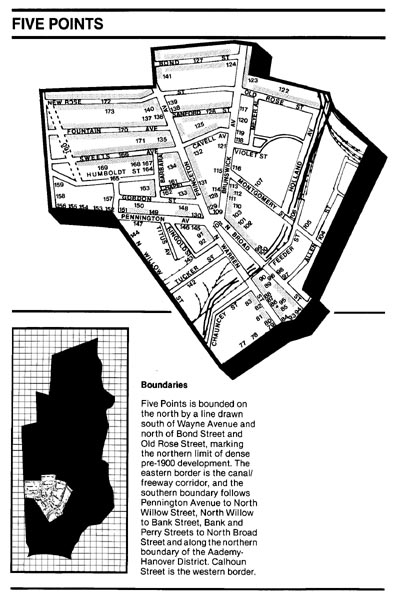

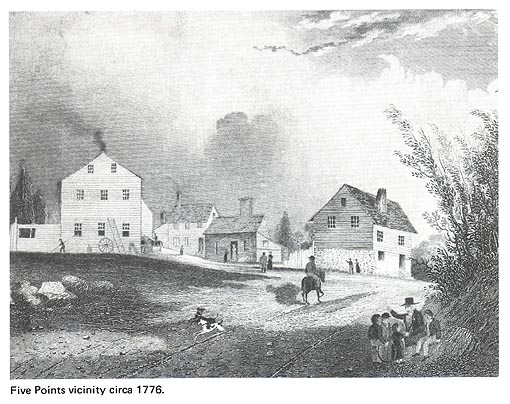

FIVE POINTS

The

Five Points area focuses on the star-shaped configuration created by the convergence

of five streets: Princeton, Pennington, and Brunswick

Avenues and North Warren and North Broad Streets.

An

entrance point to the City for most of Trenton’s early history, it functioned

as both gateway and community, dating back to the eighteenth century when

King (North Warren) and Queen (North Broad) Streets were first laid out to

converge north of the town leading to New Brunswick, Pennington,

and Princeton. Historian Harry J. Podmore relates

that, “Under the influence of traffic there came into existence at this gateway

a little community with its quaint dwellings, taverns and shops. It became

a little mart in itself:” 1 Furthermore:

“Through these highways came the early Dutch trader with his heavy pack,

the stagecoach and lumbering freight wagon, the travelling showman and magician,

the road circus and the postrider with the momentus news that patriot blood had been shed on the village

green at Lexington and that Cornwallis had surrendered

of Yorktown.” 2

The American Revolution

Five

Points saw more of the Revolution than just a postrider

proclaiming news of the most recent battle. When the Continental forces made

their surprise river crossing and early morning attack on the complacent Hessions at Trenton, General Washington and Major General

Greene and his troops marched down Pennington Road

and hurriedly set up six cannons at Five Points. From this vantage point,

artillerymen directed fire down both King and Queen Streets

toward the Hessians stationed in the center of town.

Meanwhile, General Washington surveyed the scene from an elevated field beside

Beake’s Lane (Princeton Avenue at Fountain Avenue). The Hessians, unable to offer much organized resistance, withdrew

to “The Swamp;” an area east of Montgomery Street; here they surrendered.

3 To commemorate the First Battle of Trenton

on the strategic site where Continental cannons were stationed, a monument

was constructed and dedicated with much fanfare in 1893. The Battle Monument,

(#108) designed by John H. Duncan, F.A.I.A., the architect of Grant’s Tomb,

is a one hundred fifty foot high Roman Doric column set on a large pedestal

with bronze reliefs surmounted by an observation

platform capped by a statue of Washington. The Battle Monument remains one

of the City’s most imposing landmarks, anchoring the Five Points intersection

and providing a focus for the North 25 Park.

At the same time of the Revolution, Five Points was

already considered a small community. The house of Continental soldier Thomas

Case, the Lamb Tavern, and the Sign of the Fox tavern, as well as other structures

were located in the immediate vicinity. 4

Other shops and dwellings quickly appeared, erected on North Warren and North

Broad Streets above Perry Street, connecting central Trenton with the Five

Points community.

Manufacturing: Artisans to

Industry

In

the nineteenth century, the immediate Five Points vicinity evolved as a center

for artisans. The Thomas Case house, at the fork of North Warren and North

Broad Streets, became a blacksmith shop, and was later replaced by the Valentine

Carriage and Wagon Works. A coffin maker and tin shop were located on North

Warren Street and a wheelwright and blacksmith shop on Pennington Avenue specialized in wagon bodies for nearby brickyards.

5

Early small scale industries concentrated south of

Five Points including a pottery to the rear of Lamb’s Tavern, a tannery above

Bank Street and a stone mill in “Honey Hollow” (east of North Willow Street

by the Belvidere Division railroad). This mill was

known as the “Coffee House” and was utilized for grinding spice and roasting

coffee. A millpond on Petit’s Run supplied a conduit

which turned a paddle wheel which, in turn, powered the mill. Later, however,

horse power was utilized with a “sweep,” which proved an irresistible temptation

to neighborhood boys for taking a ride. 6

However, as late as 1850, the Five Points area was surrounded to the north

and to the west by open farm country and meandering livestock.

Among the later industries was The Fitzgibbons and Crisp Union Carriage Works (#77) established

on Bank Street in 1868. The firm, housed in three and four story brick structures,

was for many years a large producer of carriages, horse drawn trolley cars,

and finally truck and automobiles bodies. The company, which exhibited at

the Centennial Exhibition, was described as “one of the most complete” manufacturers

of its kind in the country, ranking with the “great wagon manufacturers of

the Northwest.” 7

Because Five Points functioned as a commercial and

popular gateway to Trenton from the start, it was only natural that construction

of railroads with their freight and passenger depots near North Warren Street

ensued. The Belvidere-Del aware Railroad (later

the Pennsylvania Railroad line) was constructed in 1852; the Delaware and

Bound Brook Railroad branch (later a Reading Company line) followed in 1876.

Twelve years later the Philadelphia and Reading Freight Terminal (#143) was

constructed serving the industry established in this area. The Terminal, a

long elegant brick structure with a distinctive two story gable and office

wing is the sole surviving nineteenth century railroad terminal in Trenton.

As part of the North 25 Redevelopment area, it is being adaptively reused

as a senior citizen center.

Residential Development

Land

association and private developers subdivided land in the area in the second

half of the nineteenth century. Harriet Wilkinson, for instance, whose son

Ogden later became active in real estate development throughout Trenton, subdivided

land along Rose Street and Fountain Avenue. Actual development usually involved

individual lots and small tracts.

Generally, side streets feature densely-sited small,

attached vernacular houses, while main streets such as North Warren Street,

and Brunswick, Princeton and Pennington Avenues

contain clusters of more sophisticated freestanding twin and row houses.

The most notable house on Princeton Avenue is the Fell

homestead (#136) a showcase of brickwork created for Trenton’s leading brickmaking family. Both the Queen Anne main house with its

cross gables and two-tier corner porch, and the extraordinary outbuilding

behind (#137), display elaborate brick and terra cotta ornamentation. The

Fells built the sprawling Queen Anne twins at 144-154 Pennington

Avenue (#152, #154, #155) in a variation of the style of their own home. 8

The richest collection of residential structures in

the Five Points area is on North Warren Street above Perry Street (#81‑#90).

These homes lined the important approach from Five Points along Warren Street

into the downtown. Greek Revival, Italianate, Queen

Anne, Neo-Renaissance, and other vernacular variations are represented. The

large freestanding house at 221 North Warren Street (#80) was built in 1813

by Robert McNeely, mayor of Trenton from 1814 to

1832. A quite substantial house for the period, its simple Federal lines were

“embellished” with Colonial Revival and Italianate

details when remodeled in 1915. 9 The east-west connecting streets

between Calhoun Street and Princeton Avenue, including

Fountain (#170-#171) and Sweets Avenues (#166-#169) feature randomly intermixed,

simple vernacular Greek Revival/Italianate, and

Italianate/Gothic houses. These streets are so long

and narrow that even the small two and three story houses create a modest

“canyon effect.”

The foremost rowhouse groups

are 612-626 (#141) Princeton Avenue, with dormers and unusual cutout detailing

and a quite different group at 116-124 Brunswick Avenue (#110) with orange

brickwork and contrasting brownstone trim.

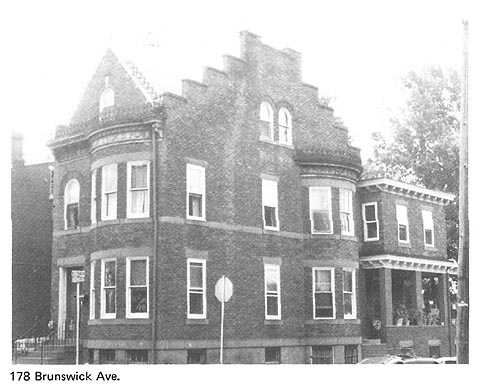

On Brunswick Avenue opposite Cavell

Street a residential cluster of more high style character and variety includes

a freestanding Second Empire structure at 194, (#120) a pre-1850 Greek Revival

twin at 184-186 (#117) (an Italianate third floor

has been added at 186), an Italianate townhouse

at 182, (#117) and a large eclectic rusticated-brick house at 178 (#118) featuring

stepped gables and rounded bays, and brownstone, pressed metal, wood and wrought

iron detailing.

Community Institutions

During

its history, many different ethnic groups have inhabited the Five Points area

and maintained community institutions. During the eighteenth century the English

settled the area. As the area developed, Five Points was settled by Blacks

in the area east of Montgomery Street, (known as “the Swamp”) and by Irish

in the vicinity of Bond Street.

The communities maintained a vital volunteer fire department,

the Harmony Volunteer Fire Department Company located on Tucker Street. Five

Points also supported an Orthopaedic Hospital housed

in several locations before construction of a building on Brunswick Avenue

in the early twentieth century. This simple yet formal Art Deco building on

Brunswick Avenue (#121) was erected on the site of the Charles May Mansion

which had been adapted to serve as a hospital.

The

Orthopaedic Hospital’s services were later merged

with Mercer Hospital. The Lincoln Public School (#107), a handsome Mediterranean

adaptation of the Romanesque style was built expressly for black children

in 1924.

The community also built several churches. The Fifth

Presbyterian Church (#131) on Princeton Avenue, a picturesque Victorian Gothic

complex, has become the Galilee Baptist Church. Our Lady of Divine Shepherd

(#149), a granite Neo-Classical structure on Pennington

Avenue, was originally constructed as a lodge.

Notes

1 Podmore,

“The Historic Five Points in Trenton.”

2 Podmore,

Trenton Old and New, p. 11.

3 Walker, et. al., A History of Trenton, pp. 149-166.

4 Podmore,

Trenton Old and New, pp. 9-15.

5 Harry

J. Podmore, “Head of Town,” State Gazette, January 26, 1910.

6 Harry

J. Podmore, “Head of Town,” State Gazette, March 29, 1920.

7 Department

of Planning and Development, City of Trenton, An

Inventory of Historic

8 Land

Development Map; “Trenton in Bygone Days;” Trenton

Sunday Times-Advertiser,

9 Vertical

File: Fraternal Organizations - Knights of Columbus, (Trentoniana

Collection,

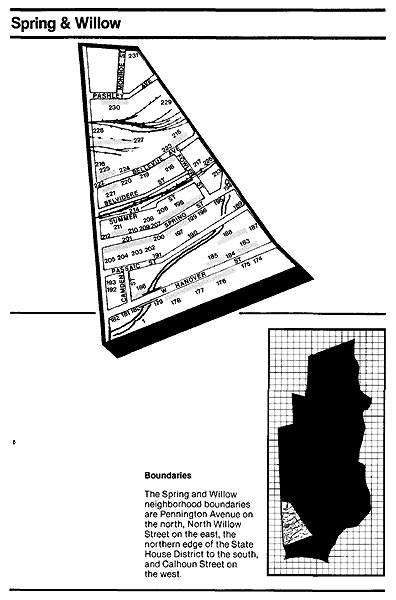

SPRING AND WILLOW

The

Spring-Willow Street area was quite rural during the Revolutionary War period.

Its leading street, River Road, now supplanted by Hanover Street, was a mere

country lane through the woods. However, the area did play an important role

in the Battle of Trenton when General Sullivan of the Continental Army marched

through it on Pennington Road and Willow Street,

forcing the Hessians into crossfire from the Continental

Army’s positions in the adjacent Five Points area. 1

After the Revolution, in 1790, Trenton was named the

state capital, and during this period, several streets, including West State

Street, were laid out. Calhoun Lane was also created

on a north-south line from Pennington Road to Beatty’s Ferry on the Delaware River, providing a link to

Pennsylvania.

With

the establishment of State Street, River Road became a primary route for the

local construction industry which transported the stone quarried amid farms

and open land west of Willow Street. Because of its direct route and proximity

to the quarries, by the mid nineteenth century, River Road became known as

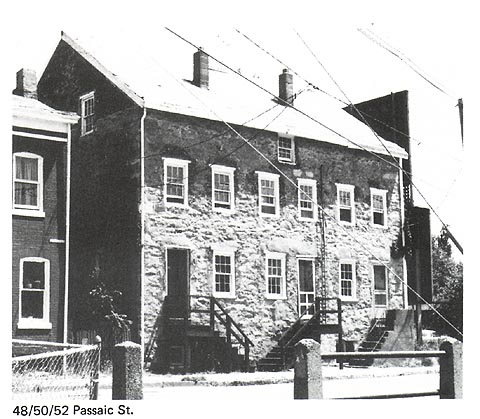

Quarry Street (later West Hanover). The “flinty grey

stone” quarried was used originally for such structures as the Old Barracks

and the building at 48-50 Passaic Street (#191), the oldest building in the

Spring-Willow area. 2 Now divided as three

dwelling units, it was originally a barn, and probably dates from the days

of land ownership of the Higbee family. Built of stone, and sited on a hillside, the

structure had a stable entrance on the downhill side, as well as a carriage

entrance at the second floor. Defined by Calhoun

and North Willow Streets, the open fields in which the barn stood were divided

from east to west by the canal feeders, railroads and streets.

During the early nineteenth century, commercial activity

shifted from actual quarrying to stone cutting and dressing. By 1834, construction

of the navigable Delaware and Raritan Canal Feeder

facilitated shipments from the outlying quarries to the Quarry Street stone

yards. John Grant operated the foremost yard on a large tract north of Quarry

Street (West Hanover), adjacent to the canal feeder. Brownstone was quarried

near Wilburtha and transported by canal to the Grant

stone yard, where it was cut, dressed and sold for construction throughout

Trenton and elsewhere. At the peak of operations, the Grant yard handled.

thousands of tons of stone at a time, utilizing its own fleet of canal and

river barges. 3 The feeder also served as

a location for other industries including the Star Chain Works and the Blackfan

and Wilkinson coal and lumber yards.

The advent of the railroads in 1852 and 1876 resulted

in two east-west right-of-ways and additional industrial development north

of Quarry Street. Both railroads have been largely removed leaving a narrow

grassy depression between Belvidere and Summer Streets

and open land which has been redeveloped as the North 25 housing project (#227).

A remnant of the days of railroad and industry is the former Wilson &

Co. meat distribution building at 283 North Willow Street (#229), which sports

a carved bull’s head projecting from the facade.

Residential Development

In

the middle and late nineteenth century, residential development occurred in

the area. Prior to such development, many canal boats wintered in the basin

at the Blackfan and Wilkinson yard, and the captains and their families

often lived aboard the ships through the winter. By the mid 1800’s, east-west

residential streets were created. Many land subdivisions also were registered

in the 1850’s by S.M. and Charles Higbee. The street

which bore the name of these developers was later changed to Bellevue Avenue.

The Wilkinson family also made reinvestments in the

area’s residential development. They developed part of the modest eastern

end of Spring Street in the 1860’s, while the western end experienced more

high style development. John Cleary’s essay “Trenton

Caught Building Lot Fever in Early ‘70’s . . .” quotes from an 1871 State

Gazette: “Although the growth of the

city appears to be eastward and

southeast, yet there are few handsomer

locations than are to be found in

all this section (Spring Street) of the city.” 4

Many houses were reported “going up” on Spring Street, and the presence of

a sidewalk on the northern side between Fowler and Calhoun

Streets received special comment. Fundamentally simple buildings given a unique

elegance by their groupings and fine detailing lined this area’s streets,

with more extravagant homes an exception.

Residential development was further stimulated by the

appearance of trolley lines on West Hanover and North Willow Streets, and

finally on Spring Street in 1885.

Spring and West Hanover Streets are still among two

of the most distinctive residential streets in the North Ward. The eastern

end of Spring Street is lined with simple vernacular, freestanding and attached

frame houses (#195-#199). A slight cant in the street marks a change in character

as large Second Empire and Neo‑Renaissance structures face each other

(#200-#210). Further west, a collection of nine elegant Second Empire twins

represents variations on a theme (#211); their bracketed entry ways topped

by gracefully curving, projecting roofs, and the corresponding mansard roofs

supported by paired brackets unify the composition. The usually simple Trenton

Italianate/Gothic twins at 96-98 (#207) share a

similar quality of the more elaborate Second Empire Twins by having wood ornamentation

in the form of pedimented window and doorway hoods,

an entryway with doubly recessed reveals and vine-like bargeboards. An imposing Queen Anne structure with a projecting

turret elegantly punctuates the corner of Spring and Calhoun Streets (#212).

West Hanover Street features handsome but very plain

Italianate/Gothic twins and has numerous clusters

of rowhouses. Adjacent to the former site of the Grant stone

yard, houses at 193-211, 204-208 (#177) and 304-316 (#186) appropriately feature

a generous amount of brownstone which lends an air of solidity and permanence.

The picturesque rowhouses built by Ogden Wilkinson

on the north side at 138-160 West Hanover Street (#183) have been described

as “patterned after Elizabethan townhouses of the nineteenth century;” 5

the Germanic influence in the roof ornament also reflects the early twentieth

century trend of European styles popularization in the United States by returning

American tourists. Whatever their precise stylistic origin, the composition,

characterized by multi-colored patterned brick and flamboyant pressed-metal

cornices makes for a unique grouping.

In contrast to the relative high style of Spring Street

and the solidity and flamboyance of West Hanover Street, a few frame cottages

exhibit simpler techniques. The structure at 82-84 Bellevue Avenue (#224),

originally built as an ice skating clubhouse, 6

is a variation on the Victorian Cottage theme and is likely to have been pattern-book

derived. Its gently gabled roofline features gracefully curvelinear trim. The otherwise austere building is enlivened

by a wrap-around porch defined by unique three-stage square wooden posts.

Jigsawn vine-like bargeboards

edge the widely overhanging eaves on four sides. This is the oldest of four

structures in the immediate vicinity bearing this vine-like detailing, found

nowhere else in the North Ward. A worker’s cottage at 120 Calhoun

Street (#192) is representative of its type with jigsawn

balustrade and bargeboards.

By the turn of the twentieth century, business had

relocated and West Hanover Street reemerged as a residential street. Around

the corner at the site of the former Blackfin and

Wilkinson coal and lumber yard, Wilkinson later laid out Wilkinson Place (#188),

constructing forty-one row houses with apartment buildings (#187) flanking

the North Willow Street entrance. 7 Wilkinson

retained total control of the enclave. Instead of selling the houses, he rented

them; instead of dedicating the new street to the city, he maintained it as

a private court. A city ordinance providing that any private street open to

the public for twenty years become public property prompted Wilkinson to periodically

close the street. Eventually, problems with municipal services dictated his

deeding the street to the city.

Community Institutions

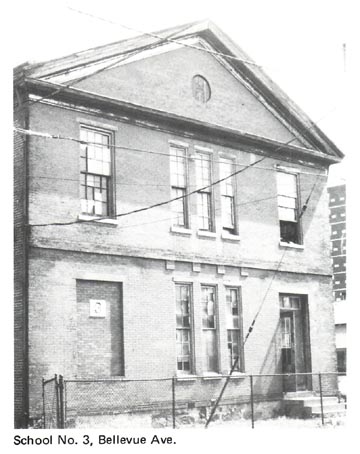

Although the Spring-Willow area was predominantly a white working class neighborhood until the twentieth century, the area’s significance to Trenton Blacks dates back to a much earlier period. In 1857, the Higbee Street (Bellevue Avenue) school (later known as the Nixon School) was constructed; it served as Trenton’s first school specifically intended for black children. This school building at 20 Bellevue Avenue (#223) is the North Ward’s finest example of a simple Greek Revival temple form structure. In addition, Shiloh Baptist Church, presently in a contemporary building on Calhoun Street (#216), organized prior to 1888, was housed in a building on Belvidere Street as early as 1897.

During the early twentieth century Black immigrants

began to settle in Trenton, and Black professionals located homes and doctor

offices on the western end of Spring Street. A 1929 article in the Sunday Times Advertiser noted that the

area was inhabited by Trenton’s middle and upper class Blacks. 8

During this period Blacks organized several additional

institutions to serve their newly increased community. St. Monica’s Mission for Colored People (Episcopal) was founded

in 1919 and subsequently established on Spring Street. The congregation later

merged with St. Michael’s.

In 1927 the Sunlight Elks Lodge I.B.P.O.E. erected

a large meeting hall at 40 Fowler Street (#217). Hosting such performers as

Cabs Calloway and Fats Waller, it doubled

as an entertainment center. A YMCA for Black youths was organized in 1927

and operated in various neighborhood buildings until it moved in 1944 into

the former Elks Lodge, rechristening it the “Carver

Center.” 9 The Center is presently operated

by the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.

1 John J. Cleary,

“Trenton in Bygone Days: West Hanover Street Has Seen Many Changes. . . ,”

Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, July 17, 1960, (Trenton in Bygone Days, vol.

12, p. 122).

2 John J. Cleary,

“Passaic Street’s Revolutionary Landmark . . . ;’ Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, March 30, 1924, (Scrapbook of Trenton History, vol. 1, p. 47).

3 Cleary,

“Trenton in Bygone Days: West Hanover Street . . . .”

4 John J. Cleary,

“Trenton Caught Building Lot Fever in Early ‘70’s; Buyers Rallied for $4,000

Prize;’ Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser,

April 10, 1921, (Memorable Yesteryears

for Trenton, vol. 2, p. 88).

5 “Unusual Buildings Mirror

City’s Past;’ Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser,

November 8, 1964.

6 Harry J. Podmore, “Trenton in Bygone Days: Ice Skating Was Popular

Winter Sport Here At Close of Civil War. . . ;” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, January 2, 1955, (Trenton in Bygone Days, vol. 10, p. 95).

7 “Wilkinson Place Has Unique

Distinction - It’s the Only Private Street in City of Trenton;’ Trenton Times, July 7, 1952.

8 John J. Cleary,

“Trenton in Bygone Days;’ Trenton Sunday

Times-Advertiser, May 12, 1929, (Scrapbook

of Trenton History, vol. 3, p. 109).

9 Vertical File: YMCA-Carver

Branch, (Trentoniana Collection, Trenton Free Public

Library, Trenton, New Jersey).

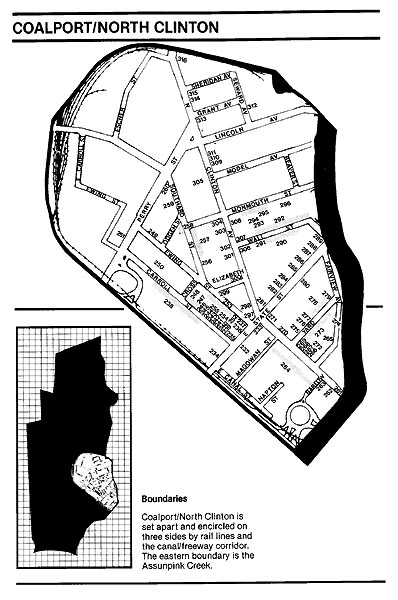

COALPORT/NORTH CLINTON

The

Coalport/North Clinton Avenue neighborhood has been

an area of contrast throughout its history. Industry grew amidst verdant farmland,

while imposing mansions stood blocks away from brick rowhouses. The earliest eighteenth century development in

the open lands to the northeast of Trenton was an iron works established by

Samuel Henry along the Assunpink Creek near East

State Street. The area developed further when Charles Higbee

constructed a mansion surrounded by pastorale countryside,

shortly after the Revolution.

Throughout the nineteenth century, land subdivisions

were registered by land associations, such as the East Trenton Land Associations,

and by private individuals including Ion Perdicaris.

However, the canal and the railroads, rather than one person or group, helped

most to stimulate development. During the early 1830’s, the Delaware and Raritan Canal was constructed, separating this area of town

from downtown Trenton. In 1839, the Camden and Amboy

Railroad and Transportation Company laid tracks that followed the canal along

the east side tow path with a station at the crossing of East State Street

and the canal. 1 The railroad offered the

first through rail service linking Trenton with New York and Philadelphia.

Across from the Camden and Amboy

rail station on the south side of East State Street, on the site opposite

the present Federal Building (#234), many impressive homes, referred to as

“Cottages;” were built during the 1840’s for Trenton’s prominent families.

These similar but distinctive squarish homes with

Greek Revival detailing featured spacious lawns. Much later, in the early

years of this century, the homes were celebrated as “once Trenton’s swellest little colony of houses” 2

These buildings are no longer extant.

In 1849, land north of East State Street was subdivided

by J.M. Raymond, W.P Sherman and Thomas Cadwalder.

What could be Trenton’s first sale of building lots soon followed. Lots were

advertised as “Near the Canal and Railroad Depots.” The neighborhood which

took shape included Carroll, Ewing and Southard

Streets, south of Perry Street.

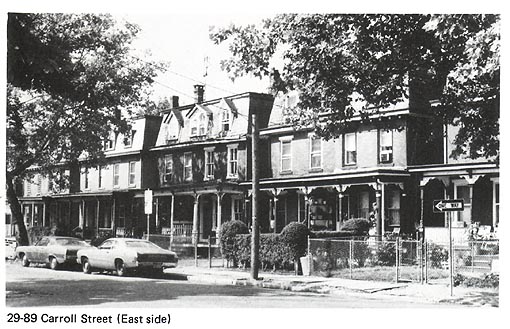

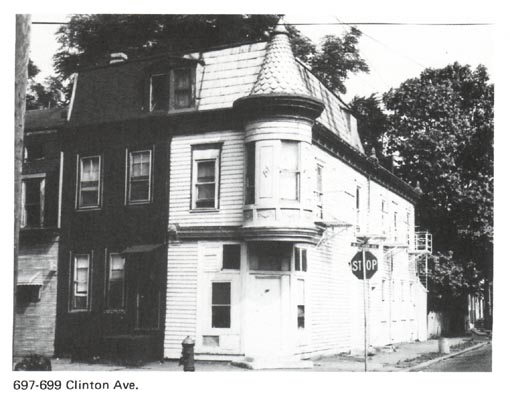

Carroll Street is lined with fifteen vernacular Second

Empire twins and structures of diverse Victorian derivation (#238-248). Six

irregular row houses at 20-30 Carroll Street (#242, #243, #244) are articulated

as twins, each twin featuring different window, porch and roof treatments.

Large inset marble blocks unite the composition. In the same vicinity, Southard

Street has Italianate twins (#257), an apartment

building with Romanesque arches (#256), and a small Greek Revival cottage

(#259).

In the 1850’s, residential development grew “into the

farm lands of Millham” when the Pennsylvania Railroad

built a second “depot” near the Assunpink Creek

at South Clinton Avenue (#265). Notable portions of the station, which was

rebuilt numerous times, include the cast iron columns and latticework hoods

of the train platforms, and the simple glazed white brick Art Deco towers.

3

The presence of the railroad station at the crossing

of South Clinton Avenue and the Assunpink Creek

also resulted in an area of specialized land use with a number of hotels in

the immediate vicinity. Hotel Penn (#263), the largest remaining is dominated

by an ornate broken pediment.

The dramatic role these railroad depots played in residential

development cannot be overstated. The growing cluster of neighborhoods including

properties on Carroll and Southard Streets in addition

to the more recently developed Yard Avenue, South Clinton Avenue, and East

State Street came to be referred to as the “Railroad Age” community. Houses

in this elite area were developed in groups so they possess similar architectural

qualities.

Yard Avenue has a split character with large Second

Empire twins on the north side (#272, #275, #277, #278), and three-story townhouses

on the south side (#272, #274). A number of individualistic dark stone and

brick Queen Anne and Romanesque inspired dwellings line South Clinton Avenue

(#266, #270). Stone of various hues and textures comprises the facade triptych

at 42-46 (#268). This stonework is a counterpoint to Trenton’s more typical

virtuoso brickwork. These homes, as well as the stone structures at 48-52

(#266, #267) were erected by Thomas H. Prior, a stone contractor. Remaining

residential structures on East State Street include massive Second Empire

(#281, #282, #284, #286), Colonial Revival (#285, #287), and Romanesque (#288)

derived houses. Comparison of Second Empire houses in the area such as 29-91

Carroll Streets (#238), 47-61 Southard Street (#258),

17-17 (#272), 18-29 (#275), 28-54 (#277-278) Yard Avenue, 55 North Clinton

Avenue (#301), and 506-508 and 528 East State Street (#281, #282), reveals

the flexibility of this stylistic theme, utilized extensively in this generally

elite “Railroad Age” neighborhood.

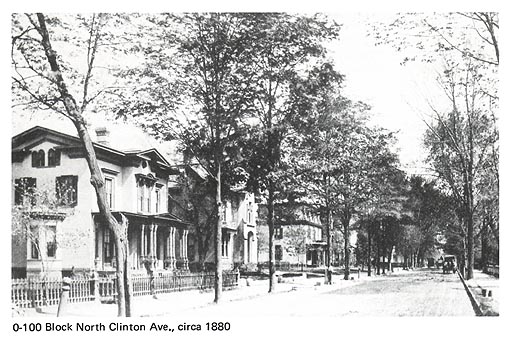

Another “first class residential district” developed

along East State Street and North Clinton Avenue. 4

North Clinton Avenue boasted many mansions, including those of diplomat-entrepreneur

Gregory Perdicaris, pottery executives James Moses, (#302) and Charles

Breadley (#303), businessmen D.P Forst and Samuel B. Packer (#304), and Mayor Welling G. Sickle.

Two-time Mayor and rubber baron

Frank Magowan built “Magowan’s

Folly (#308), an extraordinary mansion on North Clinton Avenue, but years

later, in financial ruin, he was forced to sell all of his properties and

watch his mansion dismembered.

Charles Chauncey Haven, a

visitor to Trenton in 1866, enthusiastically described the North Clinton Avenue/East

State Street vicinity in a booklet entitled “Annals of the City of Trenton

with Random Remarks and Historic Reminiscences:”

“East State Street, as it is now, extended into the country, in the vicinity

of the new depot, with the horse rail cars passing through it to the hotels

and the Delaware, running by the Cottages and the venerable row of trees planted

early in the century by Charles Higbee, Esq., and

the Fourth Presbyterian Church, a structure unsurpassed in this state as a

model of architectural beauty, present(s) a combination of advantages which

insure advanced improvements in that quart of the city. Travelers entering town often stop at the corner

of State and Clinton Streets, and are struck with admiration, bordering on

surprise, to see such charming residences and picturesque scenery in Trenton;

and if they extend their walk up Clinton Street and the elegant private mansions

and shady walks . . . their astonishment is unbounded. They go away charmed

with Trenton.” 5

At this time a passerby might have caught a croquet tournament in progress on the grounds of the Parker House or visited the favorite spot for winter sleighing on North Clinton Avenue.

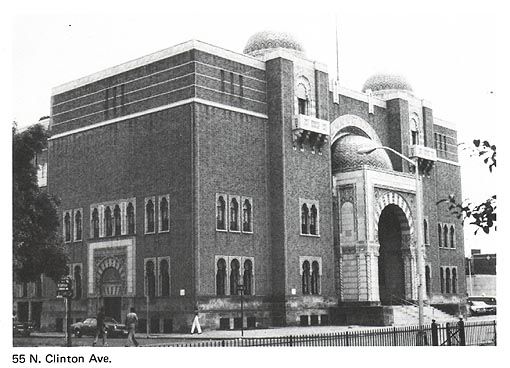

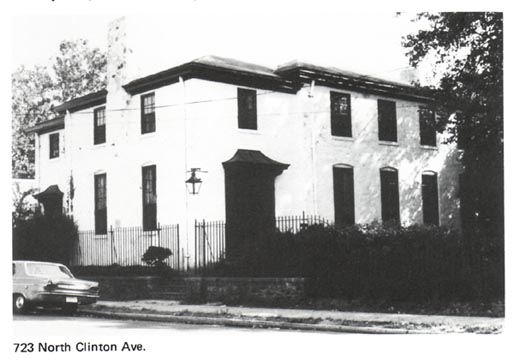

Although virtually all surviving mansions serve institutional

purposes, North Clinton Avenue has retained much of its dignity. Architecturally,

it remains the area’s premier address. The former home of James Moses, now

the Scottish Rite Temple, stands at 65 North Clinton Avenue (#302). The building

is a fantasy of stone and slate with highly picturesque roofline. The home

at 73 North Clinton Avenue, now housing the Mount Carmel Guild, is one of

the city’s finest Italianate Villas (#303). To the

north, 79 (#304) is an earlier Italianate house

with squarish massing, knee windows, and a highly

detailed brownstone and iron fence. The primary nineteenth century owner was

Samuel B. Packer, a stone and slate dealer, who left his name neatly carved

on a large stone block, just inside the front gate. He developed “Packer Row”

in North Trenton. Across the street is a deeply set back seven unit row. The

central unit, with rounded front porch, is all that remains of “Magowan’s Folly.” With some imagination, one can picture the

mansion as it was with winding stair, gold paneled ceilings, silk wall coverings,

bronze chandeliers, a music room, library, and ballroom, lengthy verandas,

gardens and orchards . . . , 6 before the

financial and political ruin of its flamboyant occupant. Not far from the

social and architectural grandeur of this area stood Coalport,

a working class neighborhood north of Perry Street. For many years the “Swamp

Angel” sat on a pedestal at the intersection of Perry Street and North Clinton

Avenue dividing the two separate neighborhoods. This Civil War cannon, fired

from the “marsh battery” at the City of Charleston during the Battle of Fort

Sumter, marked the transition between Coalport

and the more prosperous part of the neighborhood. 7

In 1961, the relic was moved to Cadwalader Park.

The Washington Building Association had subdivided

Coalport into about 300 lots for residential development in

1851. 8 At the same time industry and coal

yards marked the western portion of the Coalport

area at the juncture of the main canal and the feeder. There were canal facilities,

a railroad roundhouse, and a few potteries. The

Thomas Maddock & Sons Pottery (#249, #250),

the first major manufacturer of sanitary porcelain in the United States, stood

at the fringe of Coalport and was the most important

local industry. 9

The circa 1885 buildings are rhythmically articulated

by windows with white Italianate window hoods; the

Ewing Street building features large segmented pediments

as parapets. This “industrial complex” represents one of a number of complexes

altering the area’s residential fabric. Some are well-designed assets, while

others are nondescript intrusions.

Once narrow streets and dense residential development

characterized most of the Coalport neighborhood

populated largely by Irish. The residents fondly gave Coalport another name, Goosetown,

because of the numerous geese inhabiting the marshes. Among organized community

activities was the Thomas D. Burns Fife and Drum Corps which practiced in

front of the Burns’ Grocery. Residents also visited a makeshift circus ground

in the Yard Avenue vicinity where both Dan Rice’s and Barnum’s

circuses played. 10 The two classes met in

rather bizarre fashion when Old World Color would assail “Goosetown”

on an occasional Sunday in the warm Spring or Summer, when Mayor Welling G.

Sickle in grey top hat and appropriate suit would

drive his six horse tally-ho through Southard Street

and up over the bridge on his way to Lawrenceville

or Princeton. With a large party of friends aboard and two liveried buglers

atop the rear to herald the tally-ho’s approach,

it was always something of an event. 11

Coalport, a solid community for some

time, was, however, by the mid-twentieth century slated for urban renewal

and industrial redevelopment. The execution of this plan by the Coalport

Redevelopment Authority resulted in a radical change in the area’s character.

12

With the demise of residential Coalport,

working class housing is restricted to a small quadrant to the northeast,

and Wall Street. Lined with brick attached houses on the north side, and twin

detached frame houses on the south side, including two Worker’s Cottages with

setbacks, Wall Street is a particularly good collection of typical Trenton

housing types (#290-#293).

The North Clinton/Coalport

area also had several institutions which deserve mention. Organizations such

as the Crescent (#306) and Scottish Rite (#302) Temples, The Knights of Columbus

and the YMCA (#271) located in the area. The Mercer Cemetery (#264) was established

in the mid-nineteenth century at Trenton’s first non-sectarian graveyard.

Three Gothic brownstone churches punctuate North Clinton

Avenue. Reflecting the social character of their immediate neighborhoods,

the churches increase in size, complexity, and stylistic purity, from north

to south between Sheridan Avenue and East State Street. Unfortunately both

of the more prominent structures, the former Fourth Presbyterian and Jerusalem

Baptist, have lost their lofty spires.

The Normal School, the forerunner of Trenton State

College, and the Middle School, both teacher training schools, were built

in the neighborhood as well.

The Grant School (#305), constructed in 1938 on the

site of the state schools, is an extremely fine example of Art Moderne design. Curvilinear surfaces and metal detailing articulate

orange brick facades.

Notes

1 Walker et. al., A History of Trenton, pp. 282-283,

287-288.

2 “The Cottages Which Were Once

Trenton’s Swellest Little Colony of Houses,” Trenton

Free Public Library, Trentoniana Collection, Vertical

File: Streets.

3 The platform and elevator

towers are actually in the East Ward, connected by overhead concourse to the

main station on the western side of the Assunpink

Creek.

4 Turk, “Trenton, New Jersey

in the Nineteenth Century,” p. 228.

5 William Dwyer, “Trenton in

Bygone Days: Clinton Avenue and State Street Drew Admiration of ‘66 Visitor,” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, March 1, 1964, (Trenton in Bygone

Days, vol. 13, p. 151).

6 “Former Mayor’s Famed Mansion

Recalled,” Trentonian,

July 7, 1961.

7 Lee, History of Trenton, New Jersey.

8 “Trenton’s First Sale of Building

Lots,” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser,

September 28, 1913; Land Development

Map.

9 Department of Planning and

Development, An Inventory of Historic

Engineering and Industrial Sites, p. 8.

10 A.J. Logue,

“Trenton in Bygone Days: Goosetown Was Childhood

Home of Many of Trenton’s Best Known Citizens . . . ,” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, November 17, 1957, (Trenton in Bygone Days, vol. 11. p. 115).

11 Logue, “Trenton in Bygone Days: Goosetown

. . .

12 See Judith F Kovisars, “Trenton Up Against It: The Prescription for Urban

Renewal in the 1950’s and 1960’s”

Joel Schwartz and Daniel Prosser eds., Cities

of the Garden State: Essays in the Urban and Suburban History of New Jersey

(Dubuque, Iowa: Dendall/Hunt Publishing Co., 1977),

pp. 161-175.

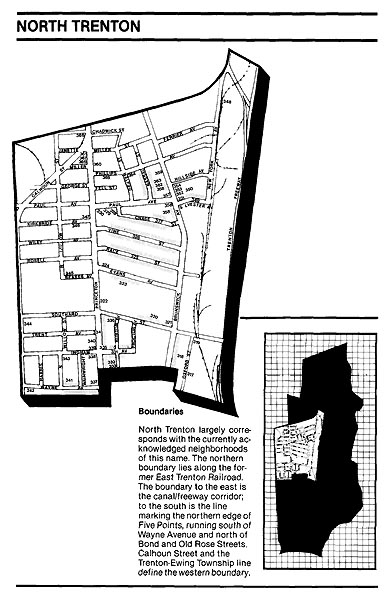

NORTH TRENTON

History and Development

Most

of North Trenton has been part of the City of Trenton since incorporation

in 1792. Narrow strips of land to the north and west, originally part of Ewing Township, were annexed in 1900. Early landowners included

the Heath, Lambert, Cadwalader and Beakes families. 1

The Nathan Beakes estate

was the earliest and best known settlement in the area, dating from Revolutionary

days. Beakes Lane ran from Five Points to the Beakes

house, which was located near the present intersection of Princeton and Beakes

Avenues. After the formation of the Princeton and Kingston Branch Turnpike

Company in 1807, the Princeton Pike followed the line of Beakes

Lane. The Brunswick or Old Maidenhead Road traversed the area to the east.

2

Despite this early estate and the highways, North Trenton developed slowly. The area’s low and swampy terrain partly explains this phenomenon. A development pattern persisted, as large tracts of North Trenton land were utilized for special purposes, part cause and part effect of slow settlement.

In 1802 a tract of higher land on Brunswick Avenue

was purchased from Nathan Beakes to be used as a

Potter’s field for burial of the poor. The “Potter’s Field” cemetery later

became known as “Gallow’s Hill” after a number of

alleged hangings, including that of a confederate spy. It officially became

the City Cemetery in 1861, retaining a ghostly reputation.

Relatively solid land was used as pastureland. A number

of tracts served as military paradegrounds. Land

opposite the Beake’s homestead was utilized in 1847

as a camp and training ground for Mexican recruits. Because of its outlying

location and available unsettled land, charities such as the Almshouse, established

in 1869, were located in the neighborhood.

The Hotel de Kelly was “a disreputable structure (sic)

dedicated to the housing of tramps.” 3 Tickets

were distributed to transients at City Hall, redeemable for bed and breakfast

after the long trudge to Kelly’s on Brunswick Avenue (at Race Street). It

was not mere coincidence that Kelly’s stood adjacent to the “Potter’s Field.”

It is said that noise and fisticuffs were common in the area. With the Almshouse,

Gallow’s Hill and the Hotel de Kelly, “it was a somewhat eerie

neighborhood.” 4

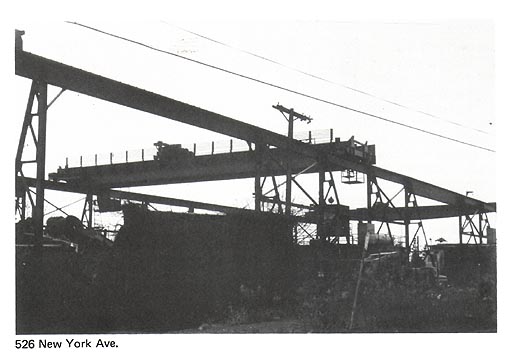

Industry

After

the construction of the Delaware and Raritan Canal,

the area attracted industries that required much space. This type of activity

included Weller’s boatyard and basin established

east of Brunswick Avenue.

The boatyard of Hiram Weller

& Sons handled jobs ranging from contracts for repair of most barges and

schooners on the Delaware and Raritan Canal, to

construction of “palatial yachts” for local gentlemen sailors. They concurrently

ran a sand and gravel business, and built dozens of flagpoles, especially

during wartime. The Weller’s basins were generally

well-stocked with barges and yachts, a few fish, and skinny-dipping neighborhood

boys. 5

H.C. Kafer

& Co., Brick Manufacturers, was also situated at Princeton Avenue and

Kirkbridge Street. They manufactured “all kinds of building

and paving brick making a specialty of pressed and fancy brick, grinding and

fitting arch brick.” 6 Founded in 1847, this

was the North Ward’s largest and most prominent brickyard, providing brick

for New York, Jersey City, and other growing municipalities, as well as the

“home market:” The office of the H.C. Kafer

& Co. brickyard still stands at 1001 Princeton Avenue (#347). A small

cubic one-story Italianate structure with bracketed

cornice on all sides, it has the appearance of a patternbook

design.

The former Jonathan Bartley

Crucible Co. complex (#317) on Oxford Street illustrates another example of

North Trenton industry. One of the structures is surmounted by three decorative

crucibles, a direct physical reminder of Trenton’s pottery prominence. Despite

the presence of industries, most nineteenth century Trentonians

perceived North Trenton as the large picnic grove of the Evans farm, or simply

as a sparsely settled outlying district along the Princeton and Brunswick

Roads, a territory to be passed through while traveling to points north. The

most commonly expressed concerns about the area included the lack of lamp

posts and the poor road conditions. 7

Rose Cottage Nurseries supplied Trentonians

with assorted flowers which complimented this country-like setting. Owned

by noted floraculturalist George Wainwright,

the nurseries occupied sizeable acreage west of Princeton Avenue and offered

a rare variety of imported Japanese tree, the Japanese Salisburia

Bibola, or the “Ginkgo.” 8

Residential Development

Eventually North Trenton residential development in the 1880’s proceeded in larger segments than elsewhere in the North Ward. Initially dwellings had been scattered about the area throughout the nineteenth century. More systematic development followed later, often taking the form of “rows” where an entrepreneur erected a series of dwellings of the same or interrelated design. Repetitive detached rows were built by Henry Phillips at 3-37 Chase Street, (#327) and Samuel B. Packer along Brunswick Avenue (#318) and Southard Street (#320).

“Packer Row” is a particularly notable late nineteenth

century example. The “Packer Row” structures provide a striking pattern along

the slight rise of Brunswick Avenue (#318). Each building, whether twin or

freestanding, two stories or three, is articulated by a continuous stone band

at sill-level, segmentally arched lintels with incised

floral motif, and a bracketed cornice.

Along Brunswick Avenue, Southard

and Oxford Street, fourteen three story twins, three simpler three story twins,

five three story row houses, a store, and a tavern were all built by Samuel

B. Packer. (#318, #319)

By the 1890’s residential development from downtown

along Princeton Avenue to the Almshouse in 1887 contributed to this development.

Henry P. Phillips purchased the cemetery site and carted away the remains,

to develop Chase Street. Subsequently, Joseph Paul opened Paul Avenue. After

1892, the trolley from downtown traversed this street, passing from Princeton

Avenue to Brunswick Avenue, then continuing northward. 9

A variety of architectural styles characterize this

residential area. Number 689 Princeton Avenue (#340) is possibly the oldest

residential structure in North Trenton; its austere form and sparse ornamentation

recalls Federal style architecture. Freestanding or twin residences exist

in a cluster at Brunswick and Paul Avenues. This grouping includes freestanding

and twin Italianate homes raised on a terrace (#358,

#359); a hip-roofed cubic house with Italianate detailing but a Greek Revival demeanor; a large

Queen Anne twin with wood shingles (#352), a Queen Anne house with sunburst

motifs and a uniquely detailed projecting side bay (#353); and a three unit

structure in bungalow style (#354). Around the corner on Sylvester Street,

a three unit Victorian Gothic structure features original weatherboards

and gingerbread detailing on one of its units (#350). This residential cluster

encompasses great stylistic variation and character on an elevated site at

the former bend of the Brunswick Avenue/Paul Avenue trolley line (#349).

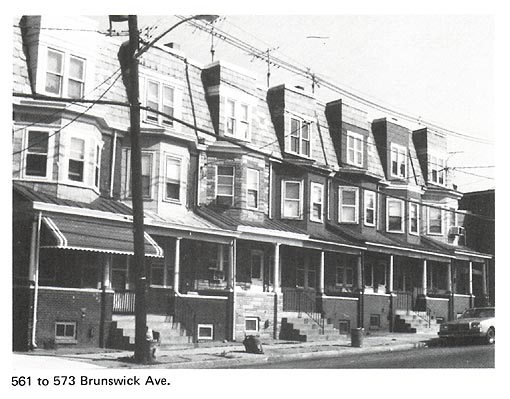

Just south of this cluster, 561-573 Brunswick Avenue

is a row of seven Queen Anne/Basic Block houses with unusual truncated dormers

(#355). Other examples of North Trenton’s distinctive series of attached houses

are 666-684 Southard Street (#320) with a continuous

metal cornice, and 1249-1259 Princeton Avenue (#367), a composition of six

interdependent units united by paired gables and parapets.

Just as in other areas and neighborhoods, construction

of the trolley line and of new schools prompted a “strong tide of improvements”

with “building in leaps and bounds” in the hands of land associations and

individual developers. 10 Approximately 200

dwellings were constructed more or less simultaneously along Vine and Race

Streets and Evans Avenue. These streets reflect the common North Ward tradition

of connecting major north-south arteries (Princeton and Brunswick Avenues)

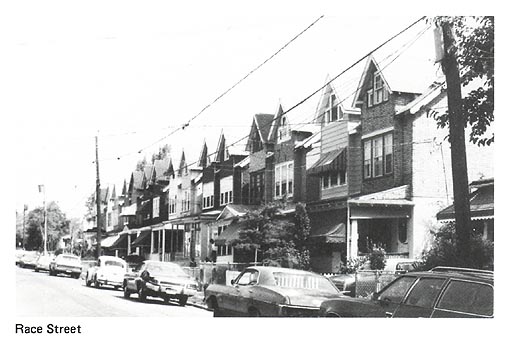

with long, continuous east-west streets. Vine Street (#326) has unusual rowhouses with bungalow detailing; Race Street (#325) is lined

with simple but dignified brick twins; Evans Avenue (#323) has Basic Block

twins; Princeton Avenue (#332-340) between Southard

Street and Wayne Avenue includes brick row houses in long series and alternating

variations on the Basic Block style. Large scale development reappeared in

the 1940’s and 1950’s public housing projects between Princeton Avenue and

Calhoun Street.

Institutions

Perhaps

because of its relatively late residential development, North Trenton does

not boast many long-standing community institutions. Dating from 1919, St.

James Catholic Church (#330) is the most prominent ecclesiastical establishment.

The Helene Fuld Hospital (#360) is a rambling complex,

originally built around one of the area’s stately mansions.

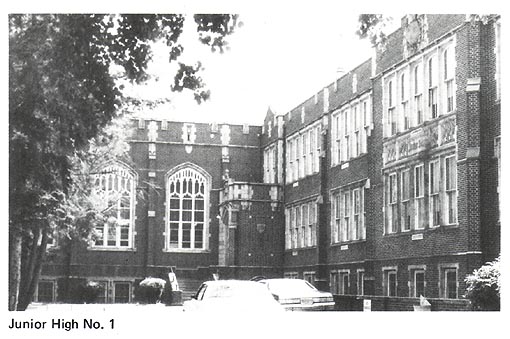

North Trenton’s Junior High School No. 1 (#322) is

a notable institution, with its elaborate Collegiate Gothic stone detailing

and its imposing structure. Following a comprehensive school system reorganization

in the early twentieth century, it was established as Trenton’s first Junior

High School. Junior High No. 1 and the Jefferson Elementary School (#321)

were constructed on the Almshouse site, maintaining much open acreage.

Today

the North Trenton area retains its characteristic blend of diverse styles

of residential, commercial, and industrial areas.

1 See Map of City of Trenton

Showing Territorial Growth, 1792-1928, Walker, et. al., A History of Trenton, p.

352. (Figure 7 of this study.)

2 Walker, et. al., A History of Trenton, p. 241.

3 Meredith Havens, “Trenton

in Bygone Days: North Trenton Area 80 Years Ago Was Bleak Section Noted For

Hotel For Tramps, City Poor Farm and Potter’s Field;” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, September 30, 1962, (Trenton in Bygone Days, vol. 13, p. 60).

4 Havens, “Trenton in Bygone

Days: North Trenton . . . :”

5 Harry J. Podmore, “Head of Town;” State Gazette, May 10, 1920.

6 ”H.C.

Kafer & Co. Brick Manufacturers,” State Gazette, July 31, 1897, (Scrapbook of Trenton Industry).

7 Harry J. Podmore, “Trenton in Bygone Days;” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, October 26, 1948.

8 Harry J. Podmore, “Head of Town;” State Gazette, February 13,

1922.

9 Trenton Free Public Library,

Trentoniana Collection, Vertical File: Street Railways.

10 John J. Cleary, “Memorable Yesteryears for Trenton, No. 33,” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, 1917, (Memorable Yesteryears for Trenton, vol. 2).

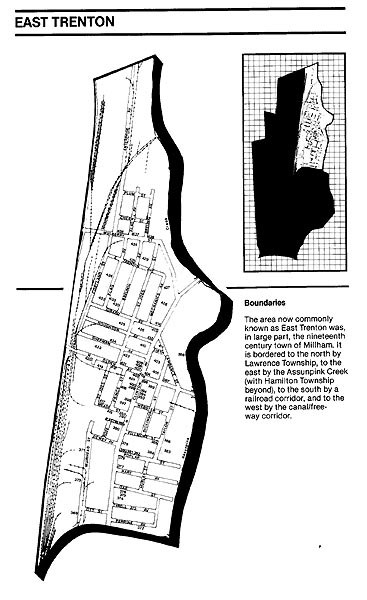

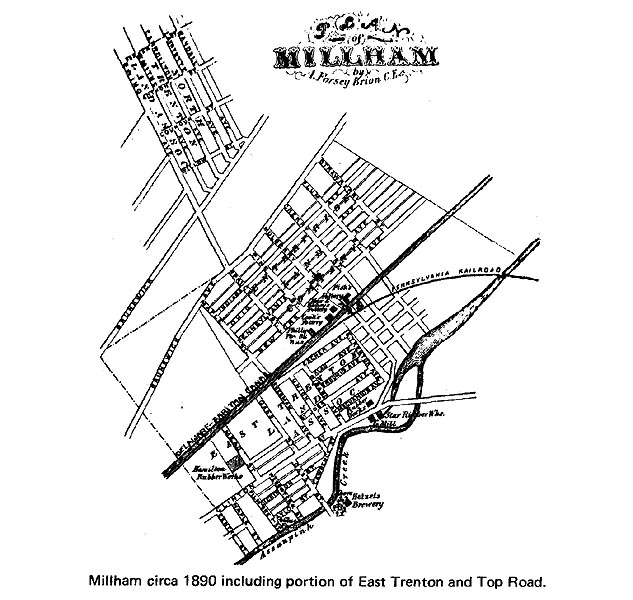

EAST TRENTON

History & Development

When

the City of Trenton first incorporated in 1792, its boundaries included the

neighborhood known as East Trenton. However, in 1844, Lawrence Township annexed

this area. It remained part of Lawrence Township until 1882, when East Trenton

became an independent jurisdiction known as Millham

Township, which included much of Top Road. On May 1, 1888, Millham

once again became part of the City. of Trenton. 1

In the mid-eighteenth century, Thomas Cadwalader owned much of Millham

Township, but it was Samuel Henry who first improved the area, building a

grist mill and planting a two hundred sixty tree apple orchard. Henry sold

his own country estate during the late 18th century to General Philemon

Dickinson. By 1797, when the estate’s eastern portion was sold, the property

included the grist mill, a saw mill, two houses, a drygoods

shop, a blacksmith shop, a kiln, a barn, stables, and 1500 fruit trees. 2

Dickinson’s son Samuel retained part of the property

in East Trenton as a country estate, constructing a stone house in 1792 known

as “The Grove,” (#414) which still remains today, and is the oldest standing

building in East Trenton. Located at North Clinton and Girard

Avenues, The Dickinson House was described in 1809 as an “excellent stone

dwelling house, 43 by 30 feet, in which there are two large parlors, the ceilings

of which are 13 feet high . . .” 3 The house

retains its original character today despite its change in use, first as a

YMCA and later as a branch library. It no longer commands a sizable estate,

but its large lot retains enough foliage to justify its historic name, “The

Grove.”

Upon his father’s death in 1809, Samuel Dickinson moved

his permanent residence to “The Grove.” Samuel’s son John attempted to initiate

an industry by cultivating silkworms and planting many mulberry trees along

the roads, especially along what is now Mulberry Street. His efforts to produce

a cash crop met with little success. 4

Despite

John Dickinson’s difficulty in establishing a successful commercial venture,

industry did arrive on the scene. By the early 19th century, the industrial

revolution began to have an impact on the area. Millham’s

industrial development depended upon and was molded by its transportation

routes. Many mills were built along the Assunpink

Creek. Industrial buildings were constructed along these routes by the 1840’s

and during the 1850’s the area’s pottery industry began to emerge.

The 1860’s and 1870’s witnessed the incorporation of

many pottery and rubber companies. The potteries,

manufacturers of products ranging from fine china to sanitary porcelain, tended

to locate near the canal, while the rubber companies scattered along Millham Road and the Assunpink.

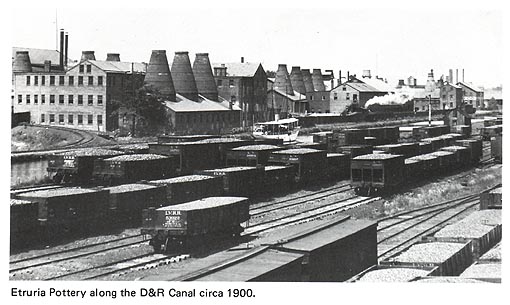

The Delaware & Raritan Canal which opened in

1838 defined the area’s western edge, creating a new industrial corridor.

The canal, the neighboring Camden & Amboy Railroad

line and Millham Road (North Clinton Avenue) to the east, all parallel

to each other, established a developmental framework. By the 1880’s a visitor

to this section of Trenton reported for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine:

“A two hours’ ride from New

York by rail takes one to Trenton, in point of production the principal seat

of ceramic manufacture in the United States. As the train enters the suburbs

one catches a glimpse of groups of substantial new buildings, whose ruddy,

flame-colored cones proclaim the great industry is striking its roots outward

from the center with its crowded factories and its network of railways and

canals. Reaching the eastern portion of the city, one is surrounded by telling

signs of the peculiar activity which has appropriately given this region its

title of the Staffordshire of America. On every

side may be seen smoking chimneys and kilns looming above tall modern factories

or long, low, weather-stained buildings, lumbering carts filled with casks

and crates of finished wares..” 5

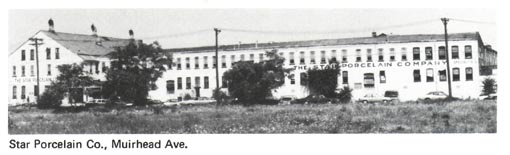

East Trenton’s physical character explains why this area

is known as “The child of industry.” Numerous two and three story brick industrial

buildings dating largely from 1880-1920 border the area. These include the

structures and complexes of the Lenox Co., (#417)

the Star Porcelain Co., (#371) the Circle F Manufacturing Co., (#415, #416)

and the John Taylor Co. (#372) (meat products). The oldest buildings of the

Lenox complex (originally built for the Ceramic

Art Co.), were designed to allow for conversion to housing should the pottery

venture fail. The complex has been expanded to include an elegant structure

with an exposed concrete frame. The Hamilton Rubber Co. buildings, (#415,

#416) presently occupied by Circle F Manufacturing Co., are a rhythmic architectural

composition of gabled 1870’s structures united by a gracefully curvilinear

wing with an Art Deco character. The John Taylor Co. buildings (#372) are

surmounted by ornate brick and terra cotta cornices.

Land Sub-Division

& Housing

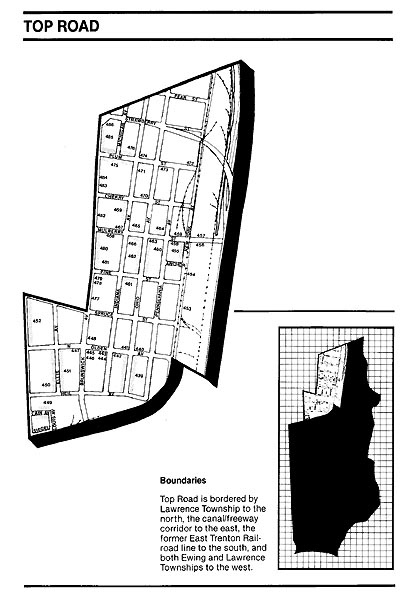

The