TRENTON TEXTILES AND THE EAGLE FACTORY:

A FIRST TASTE OF THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Richard W. Hunter, Nadine Sergejeff and Damon Tvaryanas

[Produced with funding assistance from the New Jersey Historical

Commission]

1. Introduction

Today, the crudely landscaped, grassy swale that denotes the culverted course of the Assunpink Creek between South Broad and South Warren Streets gives no clue to the profusion of industrial enterprise that once lined the stream banks in this section of downtown Trenton (Figure 1). The only hint is provided by the name of the street that parallels the Assunpink, a hundred feet or so to the south: Factory Street. Here, midway through the second decade of the 19th century, the city’s first major foray into the Industrial Revolution occurred and two of the earliest large-scale textile manufacturing ventures in the Delaware Valley took root. Just below South Broad Street, on the south bank of the creek, rose a massive five-story brick cotton mill, the centerpiece of the Eagle Factory. Immediately adjacent and downstream, a second, slightly smaller three-story cotton mill, that of the Trenton Manufacturing Company, was erected around the same time on land leased from the owners of the Eagle Factory.

Figure 1. Present day view looking northeast from South Warren

Street towards the South Broad Street crossing of the Assunpink Creek. The

grassy swale covers the filled and culverted creek. Factory Street is at the

right. The sites of the Eagle Factory and Trenton Manufactory are beneath

the grassy bank in the center of the view.

The Eagle Factory, so named for that avian emblem of American commercial and industrial vigor in the early years of the republic, was founded on the wealth of the Walns, a family of prominent Philadelphia merchants. At its peak, in addition to the brick factory building, this industrial complex also included a nearby gristmill, remodeled for picking and cleaning cotton, and a pair of weaving mills equipped with power looms. All these industrial operations were hydro-powered, drawing water from the Assunpink, while various related workshops, storehouses, sheds, a factory store and an office were scattered elsewhere across the Eagle property. The Eagle Factory expanded production quickly at first, helped by the federal government’s imposition of tariffs on imported manufactured goods, but eventually fell victim to the fluctuating economic trends brought about by regional and global competition. Flooding on the Assunpink and occasional fires further constrained the operations of both the Eagle and the Trenton Manufacturing Company cotton mills. After a generation of mixed profitability, the Eagle Factory shut down after a particularly devastating fire in 1845, with the Waln family finally selling off the mill property in 1849. The Trenton Manufactory survived past mid-century and was then reconfigured and expanded as a woolen mill that continued in operation into the 20th century (Figure 2).

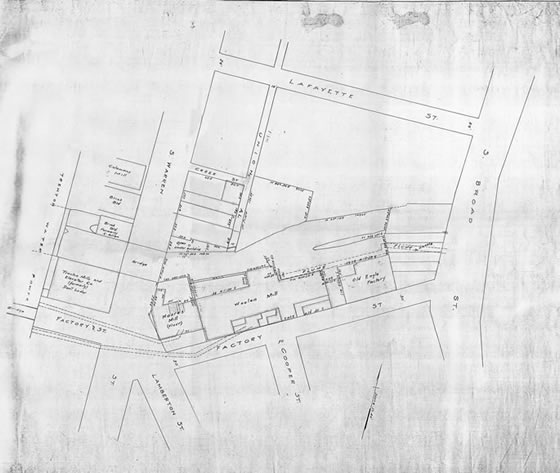

Figure 2. Map of the Assunpink Creek between South Broad and South

Warren Streets in downtown Trenton. Circa 1905. Scale 1 inch: 120 feet (approximately).

(City of Trenton Engineering Department).

This article focuses primarily on the Eagle Factory, the more dominant of

the two cotton mills on the Assunpink, and aims to place this little known

facility within the broader context of Trenton’s early industrial history,

the emerging domestic textile manufacturing sector and the Industrial Revolution

in America. The initial impetus for this study was provided in large part

by a review of the letter book of Lewis Waln and other Waln family papers

held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Lewis Waln,

a son of Robert Waln, the founder of the Eagle Factory, was involved with

the management of the cotton mill from early on in its operation and was sole

owner of the business from 1829 until 1849. His letter book bears testimony

to the day-to-day rigors of operating a cotton mill – securing raw materials,

dealing with management and labor issues, maintaining and insuring the physical

plant, and establishing prices and markets for the manufacturing goods. Along

with other standard sources for this period, such as census data, deeds and

mortgages, newspapers and historic maps, the Waln archive provides a rich

lode of documentary material about the early years of textile manufacture

in the Delaware Valley.

2. The Genesis of the Cotton Industry in America

As the new republic began to set foot on the world stage as an independent player-nation in the final two decades of the 18th century, the need for a strong domestic manufacturing base, particularly with regard to textile and metal products, was immediately appreciated among politicians, merchants and industrialists. From an American perspective, profitable textile manufacturing was necessary both to clothe and provide work for the country’s rapidly growing body of inhabitants and to nourish trade inside the country and beyond.

By the late 1780s and early 1790s, British textile producers were already far more advanced in the mass production of cotton cloth than their American counterparts and were beginning to monopolize United States and global markets. By 1767, James Hargreaves had invented the “spinning jenny,” which enabled a single worker to simultaneously produce several yarns. In 1769, Richard Arkwright patented his “water frame,” a water-powered machine that was well suited to producing large quantities of coarse twisted warp yarn. Two years later, Arkwright put his first water-powered spinning mill into operation at Cromford in Derbyshire, England, soon after adding carding machinery and thereby ushering in an entirely new type of factory, where mechanical integration propelled mass production. In 1779 Samuel Crompton perfected the “spinning mule,” a machine that combined elements of the spinning jenny and water frame and produced the finer yarns used as weft on the loom. By 1786 Edmund Cartwright had invented a steam-powered loom and much improved carding machinery; and advances were also being made around the same time in the application of water and steam power to several other late-stage textile manufacturing processes, such as printing and fabric finishing. By 1788 no less than 150 water-powered cotton mills were in operation in Britain, mostly engaged in carding and spinning; there were none in the United States.

American industrialization of cotton manufacture commenced in the early 1790s and evolved out of important developments in both the initial processing of the raw material on the cotton plantations and the realm of manufacturing. In the former case, the key event was Eli Whitney’s invention in 1793 of the cotton “gin,” a boxed revolving cylinder with spiked teeth that separated the bast fiber from the seeds, hulls and other material that make up the cotton plant. Initially driven by a hand-operated crank, but soon horse-powered and water-powered, this item of equipment permitted substantially greater quantities of cotton to be shipped from the southern plantations to cotton mills in the emerging industrial centers of Europe, New England and the Mid-Atlantic.

Insofar as the actual production of cotton cloth was concerned, the mechanization of cotton manufacture in the United States followed a pattern of technological, socio-economic and geographical development that was broadly similar to and strongly influenced by that in Britain. Mechanization in the United States began a decade or two later than in Britain, but was embraced rapidly, even though in some locations, like Paterson, New Jersey, the move toward integrating processes within a single building was much slower. However, the overall sequence of industrial development was compressed into a shorter time frame, such that by the mid-19th century, cotton manufacturing on both sides of the Atlantic had attained a roughly equivalent level of technological competence and scale of operation.

In the Middle Atlantic states, a group of Philadelphians, inspired by the merchant and political economist Tench Coxe, founded the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts in 1787. Cotton manufacture was of acute interest to society members as a potential source of economic development. Using inadequately understood sketch plans and models, plans for a cotton mill were drawn up and a building was erected, but the owners’ poor grasp of the operational requirements, financial difficulties and a disastrous fire derailed the project in 1790. Coxe, by this time an assistant to Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, switched his attention instead to gaining information about British cotton-manufacturing technology by luring mechanics with the necessary know-how to the United States.

It was as a result of this latter effort, which at times bordered on industrial espionage, that Arkwright’s cotton spinning technology was finally introduced into the United States in the early 1790s. Despite British controls on the export of machinery and the emigration of skilled cotton workers and millwrights, Samuel Slater, an English mill overseer familiar with the Arkwright textile production system, succumbed to the temptation of American bounties offered for the introduction of cotton manufacturing technology. Arriving in New York late in 1789, Slater moved to Rhode Island in January of the following year at the urging of Moses Brown, a wealthy Quaker merchant in Providence. By December of 1790, Slater had recreated from sketches and his own experience a range of carding, drawing, roving and spinning machinery sufficient to attract American investors. In 1792-93, he built the first successful cotton mill in America on the Blackstone River in Pawtucket with the backing of the Providence merchant firm of Almy & Brown. Within 15 years, several more water-powered cotton spinning mills were established along the Blackstone and other rivers in Rhode Island, southern Massachusetts and eastern Connecticut.

Tench Coxe, meanwhile, used his experience with the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts to prevail upon Alexander Hamilton and other leading New Yorkers to launch another high technology initiative in 1791 known as the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.). An ambitious scheme was soon hatched for large-scale cotton manufacture based around the water power available at the Great Falls of the Passaic River in northern New Jersey. In addition, an entire new industrial town, not unlike Robert Owen’s model industrial settlement of New Lanark, was envisaged. Although the Great Falls venture initially foundered for want of capital and was incompetently managed, the seeds were sown through this project for the early 19th-century growth of Paterson as a textile-producing center.

By the end of the first decade of the 19th century, more than 60 cotton mills turning more than 30,000 spindles were in operation in the United States, with particular concentrations of textile manufacture in evidence in Rhode Island and in the Middle Delaware Valley in and around Philadelphia. Industrial operations in cotton factories during this period were mostly limited to carding and spinning. Weaving was usually done off the premises on handlooms and on consignment, while other late-stage processes like bleaching and calico printing were also conducted in separate establishments.

From 1807 through the War of 1812 (which continued until 1815), successive American embargoes on foreign goods, intended to force an end to restrictive British and French trading practices, cut the United States off from much of its profitable foreign trade and closed the door to imported British textiles. The harsh reality of potential clothing shortages, unused merchant capital, and shipping lying idle in east coast port cities like Boston, Providence, New York and Philadelphia prompted a surge of American investment in domestic textile manufacturing enterprises. This led to a rapid increase in the number of cotton mills along the major drainages of the eastern seaboard, most of these facilities again still being engaged chiefly in carding and spinning.

During the second decade of the 19th century, power loom technology – already known in England for a quarter of a century – finally made its way to the United States (Figure 3). The introduction of the power loom into American cotton mills, and its incorporation within the nation’s emerging factory system, was primarily a result of the efforts of the prosperous Boston merchant, Francis Cabot Lowell, who visited the Manchester area in England in 1810-11. Returning home in 1812, Lowell founded the Boston Manufacturing Company and established a mill in Waltham, Massachusetts. By 1814, with the help of mechanic Paul Moody, he had succeeded in reproducing the power looms he had seen in England and, still more important, had integrated the three main cotton manufacturing processes – carding, spinning and weaving – under the same roof. These accomplishments set the stage for the creation of the mill town of Lowell on the Merrimack River in the early 1820s and the phenomenal growth of textile manufacturing in New England in the second quarter of the 19th century. The Waltham-Lowell system, as it became known, also spread rapidly into the Middle Atlantic region, helping to revive the foundering mill town of Paterson in the 1820s and 1830s and spurring several textile manufacturing ventures in the Delaware Valley, among them the Eagle Factory in Trenton.

Figure 3. Typical view of power looms in operation in a cotton mill

of the mid-1830s (Edward Baines, History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great

Britain [Fisher, Fisher and Jackson, London, 1835], 239).

Technological advances continued to be made in the period between 1815 and 1850, both in refining and integrating the various cotton manufacturing processes and also in developing more efficient generation and application of hydropower. Printing, bleaching and dyeing of fabrics all became more closely incorporated within the factory system. The design of breast wheels and, most especially, turbines were dramatically improved through the efforts of Lowell engineers such as Uriah Boyden and James B. Francis. Leather belting, used first on a large scale in the late 1820s by Paul Moody at the Appleton Mills in Lowell, soon emerged as a quieter, faster and less jarring means of transferring power to the carding machines, mules and looms spread throughout the mill buildings, and was infinitely preferable to the machine gearing and shafts used in earlier mills.

Even though the steady progress of technology drove the American textile

manufacturing to an ever-greater production capacity in the decades following

the War of 1812, the industry still struggled mightily to compete with European-made

fabrics. Beginning in 1816, and continuing into the 1840s, the federal government

passed a series of protective tariff acts that levied duties on imported textiles.

These charges were intended both to encourage domestic production and help

offset interest payments on the heavy debts incurred during the recent war.

The price of coarse cottons fluctuated wildly in the years that followed,

but in a mostly downward direction, diving to as little as 8½ cents

per yard in 1829. Concurrently, growing unhappiness with the cost of American

cotton caused the British to look to other providers and markets, thereby

threatening the livelihood of raw cotton producers in the southern states.

For the most part, the booming New England textile industry was able to benefit

from the protectionist legislation and overcome the global economic pressures,

continuing on its upward trajectory of prosperity. In the Middle Atlantic

region, successful textile manufacturing proved more of a struggle, and the

travails of dealing with broader economic issues eventually contributed to

the demise of the Eagle Factory and many other cotton mills in the Delaware

Valley.

3. Trenton Textile Manufacture in the Early 19th Century

Trenton’s first venture into industrialized textile manufacture was hardly a spectacular success. In 1812, Josiah Fithian, a cabinet maker living on Second (today’s West State) Street, a few doors east of the New Jersey State House, set about establishing a cotton factory on Petty’s Run, a minor tributary of the Delaware River that flowed through his property. Borrowing heavily, Fithian erected a mill on the north side of the Front Street crossing of Petty’s Run on the site of an earlier water-powered plating mill and steel furnace (Figure 4). As the Trenton historian John Raum reported several decades later, Fithian “had completed the walls, put on the roof, and was about putting in the machinery for a cotton mill, when a heavy rain undermined the foundation, and the mill fell with a terrible crash – a mass of ruins. He rebuilt it, put in machinery and commenced the manufacture of cotton cloth. He continued here, however, but a short time, when he sold out to General Garret D. Wall, who converted it into a paper mill …”

How long the Fithian cotton mill stayed in operation, what type of machinery was in use and what kinds of cotton products were being made are all questions for which no clear answers have been found in the archival record. By 1819 Fithian was in financial difficulty and ownership of the cotton mill property had passed to his brother-in-law and creditor, Jacob Scudder. A sale notice for the mill published in this year by Scudder notes that the premises were “occupied by Mr. Gideon H. Wells,” one of the partners in the Eagle Factory, although it is unclear if Wells was actually engaged in manufacturing on the site. It is possible that the cotton factory built by Fithian ceased operation around this time. In 1823, the site was acquired by Garret D. Wall, which may represent an approximate start-date for the paper mill. Based on the technology available in the United States in 1812, the Fithian cotton manufacturing venture most likely involved the carding and spinning of yarn for local distribution to weavers using handlooms.

In the meantime, in 1814-15, two larger and more durable cotton factories, and also a woolen factory, took root on the Assunpink Creek below Greene (modern South Broad) Street, roughly 1,000 feet to the southeast of the Fithian mill (Figure 4). The larger of the two cotton manufacturing facilities, the Eagle Factory, established by the Waln family of Philadelphia, is the principal subject of this article and is discussed in greater detail below. The other cotton mill was erected by Lawrence Huron & Company immediately downstream of the Eagle Factory on land leased from Gideon Wells, brother-in-law of Robert Waln and his partner in the Eagle Factory. These two mills – the Eagle Factory and what soon became known as the Trenton Manufactory or the Trenton Cotton Factory – became closely intertwined. The latter was eventually owned by James Hoy, formerly a superintendent at the Eagle Factory, while the water power for this mill was for many years drawn from the same millpond that supplied the Eagle Factory and flowed through the Eagle Factory property.

It is not known which of these two mills – the Eagle Factory or the Trenton Manufactory - came on line first, and one wonders how intense the competition was between them. By September of 1815, the Trenton Manufactory was looking to hire apprentice weavers and advertising for sale “Cotton Twist and Filling of a superior quality, from No. 4 to No. 40,” cotton shirting and cotton sheeting. Most likely, during this period, both the Trenton Manufactory and the Eagle Factory, like the Fithian cotton mill, made use of water-powered machinery for picking, cleaning, carding and spinning in a minimally integrated fashion, and relied on workers using handlooms, probably both on and off-site, for weaving. Power looms were introduced at the Eagle Factory by at least 1821 and were present at the Trenton Manufactory before 1826, suggesting that these mills were being influenced quite early on by the Waltham-Lowell system.

The Trenton Manufactory, however, was struggling in the 1820s and the mill and its machinery were subject first to a sheriff’s sale and then a public auction in early 1826. The notice for the sheriff’s sale provides the first detailed information about this factory, describing a three-story brick building, 80 by 40 feet in plan, which included a dye house and blacksmith shop, in addition to a range of textile machinery that included four throstle (thread-spinning) frames, stretchers, carding engines, eight power looms, two wrapping mills and two mules with 258 spindles.

The federal manufacturing census compiled in 1833 for what was then referred to as James Hoy’s Trenton Cotton Factory reveals a subsequent upgrading of the weaving operations, noting along with other useful data that a steam-powered weaving shop had been established in 1829. In 1833, the capital invested in the cotton spinning mill was given as $69,000, and in the new weaving shop as $32,000, while the water power used in the former facility (leased from Gideon Wells and Lewis Waln) required an annual payment of $600. Hoy reported borrowing $20,000 at a 6% rate of interest in support of the mills, and the profit on the un-borrowed portion of the investment was given as 3% per annum. Products were chiefly marketed in Philadelphia and sold by commission at six to eight month’s credit, with 5% to 7.5% for commission and guarantee. The early 1830s were clearly a difficult time for textile mills and, as reflected in the census data, Hoy’s operations produced little profit. In response to the query as to what he might do with his capital if forced to abandon his business following a lowering of tariffs on imported textiles, Hoy replied that he would employ his capital “in no other way, having none left. If I, who have been long in the business, would have to abandon it, who would purchase my property? It would be the most unproductive stock in the United States; I could not sell it.”

The history and location of the third textile factory to emerge on the Assunpink in the second decade of the 19th century are poorly understood. A series of newspaper notices between 1814 and 1816 refer to a mill seat that was initially developed for a woolen factory by John Denniston. Described as being located a quarter to a half mile from the “market house,” this mill is believed to have been situated downstream of the Trenton Manufactory and opened for business over the winter of 1814-15, offering to full, dye and dress wool cloth (Figure 4). Other manufacturing processes were later added, as evidenced by an advertisement of May 25, 1816 in which the “Woollen Manufactory of Trenton” was attempting to sell off all of its equipment, including “Carding, Spinning and Shearing Machines, Screw and Press, Looms, Kettles and a variety of other articles used in the factory.” This notice, placed by Ellett Tucker, a Greene Street storeowner, and Gideon H. Wells, the Eagle Factory partner, implies that the woolen factory had fallen on hard times. The factory fades into obscurity after this time.

Just a few years after the founding of the three factories on the Assunpink, another important thread in Trenton’s early 19th-century textile industry emerged on the banks of the Delaware at the foot of Federal Street, about a half mile downstream from the mouth of the Assunpink (Figure 4). In 1817, a calico printing factory was erected here by John B. Sartori on his riverfront estate, a property centered on a fine federal dwelling known as Rosey Hill. Sartori (1765-1853), the son of a jeweler to the Pope, was born in Rome and emigrated to Philadelphia in 1793. Best known as the first United States consul to the Vatican, an appointment he received in 1797 from President John Adams, Sartori lived at Rosey Hill from 1803 until 1832, during which time he was a prominent and colorful figure in Trenton society, and a local leader of the Catholic church. While in Trenton, he also displayed an entrepreneurial streak, which was reflected in his dealings with the Philadelphia shipping merchants, Jeremiah and William R. Boone, in his manufacture of pasta (also conducted on the Rosey Hill property), and in his prolonged involvement in the printing of cotton cloth.

Along with Peter A. Hargous, a member of another wealthy local Catholic family of French origin, Sartori formally incorporated his calico printing business in 1820 as “The Trenton Calico Printing Manufactory of Bloomsbury.” The company was set up specifically for the purpose of manufacturing and printing wool, cotton, silk, flax and hemp. As the corporate name implies, however, calico, which in its narrowest and most widely understood sense referred to printed cotton cloth, was the main focus of the business. The source of the cloth being printed at the Bloomsbury works is uncertain, although it seems likely it took in fabric from the various nearby cotton and woolen mills on the Assunpink and Petty’s Run.

The Trenton Calico Printing Manufactory continued in operation through into the late 1820s, but one suspects it was not a highly profitable concern. In 1829, a court judgment was made against the company in favor of Jonathan L. Shreve and George Potts for $6,000. At that time, Peter A. Hargous and Stacy A. Paxson were listed as directors, William Potts was serving as President, and Samuel L. Shreve was the Treasurer. Sartori is conspicuous in his absence from the roster of officers, and one wonders if he had divested his interest in the company by this time. The Trenton Calico Printing Manufactory fades into obscurity following the court judgment of 1829 and the firm was perhaps dissolved soon after.

One final focus of milling activity in Trenton deserves a brief mention within the context of the city’s textile manufacturing aspirations. On the banks of the Delaware River close to the William Trent House, roughly midway between the Sartori property and the mouth of the Assunpink, an important mill complex known mostly as Daniel W. Coxe’s Mills or the Bloomsbury Mills emerged in the second decade of the 19th century, drawing its power from a wing dam in the Delaware (Figure 4). The first and primary facility in this complex was a merchant gristmill, which effectively superseded the city’s original grain processing site at the South Broad Street crossing of the Assunpink (where the Eagle Factory was soon to arise). By 1819, according to an advertisement in the Trenton Federalist, the upper part of the Coxe gristmill was being used for wool carding, a hint perhaps that textile operations were spreading into all available milling spaces in the city.

Clearer evidence that Coxe, a brother of Tench Coxe, had been interested in expanding his milling activities beyond grain processing into manufacturing is provided in a sale advertisement for his entire Trenton estate issued on March 21, 1825. In addition to the gristmill, this sale notice references a second, recently built and adjoining three-story stone mill of roughly similar size that is described as “now ready for the reception of any description of machinery.” A contemporary watercolor by Robert Montgomery Bird, produced on July 24, 1826, shows the disposition of these two mills, with the later structure looking well suited for use in textile manufacture. The ultimate use and fate of this section of Coxe’s Mills remain unclear, for within a decade or so this stretch of riverfront became the scene of intensive mill development and redevelopment brought about by a large hydro-engineering project that radically changed much of downtown Trenton.

This project, which provided an important, albeit short-lived boost to Trenton’s textile industry, involved the construction of a seven-mile-long power canal along the left bank of the Delaware River to bring water into the downtown and the Bloomsbury/South Trenton area, and specifically to encourage the development of mill sites for manufacturing purposes (Figure 4). Built by the Trenton Delaware Falls Company in 1831-34, this urban water power spurred the development of close to 20 mill sites over the following twelve years, although this was considerably less than the number originally envisaged. In part because the potential of the power canal was never fully realized, and in part because of indebtedness incurred from the canal’s construction and maintenance, the Trenton Delaware Falls Company went bankrupt in the early 1840s. The waterway was subsequently co-opted by Peter Cooper and the Trenton Iron Company and reconstituted as the Trenton Water Power, continuing in use through the remainder of the 19th century and serving a handful of textile mills in addition to the rolling mills of the Trenton Iron Company (later the New Jersey Steel and Iron Company) and various other facilities.

James Hoy’s Trenton Cotton Factory was one of the first mills to take advantage of the new power canal, reconfiguring its hydropower system in the mid-1830s to draw water via a headrace that tapped the canal just below the aqueduct that carried the water power over the Assunpink. Hoy also purchased the land on which the factory was built from Lewis Waln in 1834, a property transfer that was likely connected to the Trenton Cotton Factory’s reconfiguration of its hydrosystem (the factory probably ceased using water from the Eagle Factory millpond at this time). Hoy’s cotton mill, in 1837, was valued at $75,000, drew a 250 square-inch head of water from the power canal and was producing 300,000 yards of cotton goods annually. The factory possibly suffered a contraction in its business as a result of the Panic of 1837 and the national economy’s subsequent lean years. More certain is the devastating effect of the Great Flood of January 1841, which took a heavy toll on many Trenton homes and businesses. A contemporary newspaper account reports that “[t]he dye house and lower story of Mr. Hoy’s Cotton Factory were flooded for several days.” The factory returned to full production and continued under Hoy ownership until 1852, when it was sold to Samuel K. Wilson, following a fire in the preceding year. Under Wilson ownership, the mill switched its emphasis to woolen manufacture and operated into the 20th century.

The power canal of the Trenton Delaware Falls Company supplied the impetus for several other textile mills and related industries in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Just downstream of Hoy’s cotton mill, below Warren Street, a bone button factory was erected in 1836-37 by Samuel Croft and Daniel Lodor. Around the same time, a branch raceway was constructed linking the main power canal to the Bloomsbury Mills adjacent to the William Trent House (then occupied by Governor Philemon Dickerson, a strong supporter of textile manufacturing in Paterson). A series of new mills appeared along the branch, among them a textile factory known as the Orleans Mill, which later came under the control of Samuel K. Wilson.

At the downstream end of the power canal below Federal Street, the Union Manufacturing Company built a cotton printing works on the site of the old Trenton Calico Printing Manufactory in 1837, adapting the old calico works “on the Sartori Place” so that it could make use of water power (Figure 4). This business was joined in 1842 by the cotton mill of the New England Manufacturing Company of South Trenton, a firm incorporated for the purpose of “manufacturing, bleaching and printing all goods of which cotton or other fibrous materials form a part.” Two or three years later yet another cotton mill was erected nearby by Andrew Allinson. The Union print works was destroyed by fire in 1850, while in 1854 the property occupied by the New England cotton factory was acquired by the Trenton Iron Company. By 1856 both mill sites were subsumed within the latter’s rapidly expanding rolling mill complex. The Allinson mill, however, shifted into woolen production, becoming known as the Saxony Woolen Mill, and continued in operation into the early 20th century.

The one textile manufacturing facility that did not hook up to the Trenton

Delaware Falls Company’s power canal was the Eagle Factory, which because

of its location further upstream along the Assunpink was not in a position

to draw off water power from the new canal. The Eagle Factory mills were fortunate

in having their own millpond and hydropower system, independent of the power

canal, although it is unlikely that this enabled them to function any more

productively than their competitors. Prior to the construction of the power

canal, the Eagle Factory was indisputably the dominant textile manufacturing

concern in Trenton; following the completion of the power canal, the Eagle

influence waned and the factory was up for sale by the mid-1840s.

4. The Waln Family Enterprises

Although the footings laid for the Eagle cotton mill in 1814-15 were likely constructed of local Wissahickon schist, the true foundation of the Eagle Factory was wrought from the personal fortune of Robert Waln (1765-1836) (Figure 5). Robert was the great-grandson of Nicholas Waln (circa 1650-1721), the progenitor of the Waln family in America. Nicholas arrived in Pennsylvania in 1682 making his transatlantic crossing aboard the Welcome in the company of William Penn and securing a spot for his family in the upper levels of Pennsylvania’s Quaker aristocracy. Robert Waln’s father, also named Robert, was a prosperous Philadelphia merchant and ship owner. He died in 1784 leaving his son both considerable wealth and the difficult task of resolving the family’s accounts and winding up the affairs of a merchant business of international complexity.

Figure 5. Early 19th-century portrait of Robert Waln attributed to

Robert Eichholtz (Ryerss Museum, Fairmount Park Commission, Philadelphia).

The year after his father’s death in 1784, the younger Robert Waln entered into business with his cousin Jesse Waln and Richard Hartshorne. Robert quickly set about establishing his own reputation in the merchant community. In 1788, he, Jesse Waln, Pattison Hartshorne and Ebenezer Large entered into a series of partnerships and formed two separate but closely associated firms, Jesse and Robert Waln and Hartshorne and Large. This arrangement lasted for a decade but, in 1798, the partnership of partners was terminated leaving the firm of Jesse and Robert Waln operating independently as one of the major players on the Philadelphia waterfront.

From their counting house at the foot of Spruce Street (Figure 6), Jesse and Robert Waln oversaw a mercantile network that extended across the Atlantic to the West Indies, England and beyond. Initially, most of their activities were focused on trade between Philadelphia, London and the Caribbean. These were the venerable and well-tried routes of earlier merchant generations founded on the triangular trade network of imperial Britain and colonial America. However, as the 18th century drew to a close, the merchants of the fledgling United States looked east to the emerging markets of China and the East Indies. Beginning their investment in the Canton trade in 1796, Jesse and Robert Waln were among the first of Philadelphia’s large merchant firms to recognize the potential for trade in the Far East.

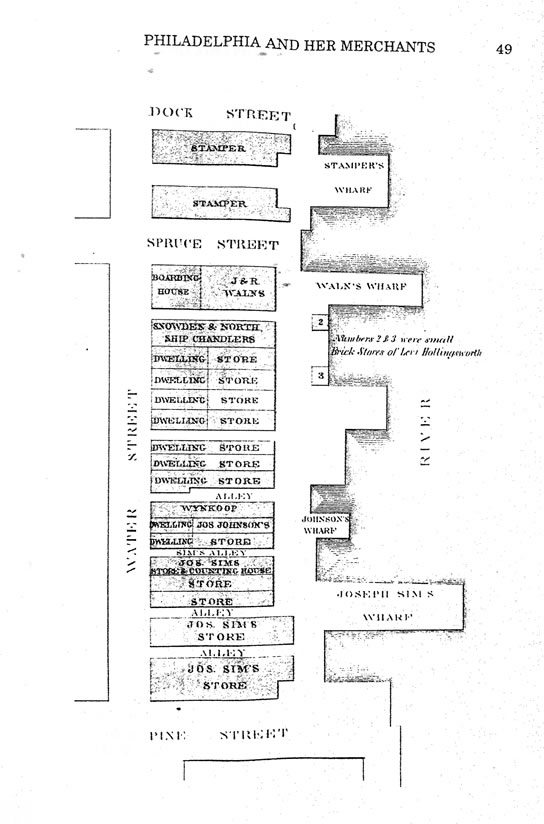

Figure 6. Map of the Philadelphia waterfront showing the location of Waln's wharf (Abraham Ritter, Philadelphia and Her Merchants [Abraham Ritter, Philadelphia, 1860], 49).

During this period Robert Waln assumed considerable political prominence, serving first on the Pennsylvania State Legislature (1794-98) and then in the United States House of Representatives (1798-1801). The firm of Jesse and Robert Waln continued in business until 1805 when Jesse Waln withdrew from the company. Perhaps Jesse’s decision was based on deteriorating health for he passed away within a year of turning over his share of the firm to his brother. Although Robert stated that his mercantile activities decreased in the wake of Jesse’s death, over the course of the next decade, he went on to send more than 45 ships on long trading voyages, most bound for the Orient. Nevertheless, the purported reduction in Robert Waln’s trading activities after 1806 corresponded with broader trends affecting American involvement in the global economy. European conflicts and increased British interference in American commerce led to a more than 50% drop in the combined value of United States imports and exports in the years between 1806 and 1812.

The outbreak of the War of 1812 only exacerbated the international trading problems of Philadelphia’s merchants. On December 26 of 1812, the British navy was ordered to implement a blockade of the Chesapeake and Delaware bays in an attempt to place a stranglehold on American commerce. Although the ultimate effectiveness of the blockade has been debated, by the end of 1813, United States imports and exports had fallen to less than half of their levels in 1811, a staggering blow to the national economy considering that American trade had already dropped significantly prior to this date. Yet worse was still to come. In the spring of 1814, the British navy sent ships into the busy waters of New England and thus extended their blockade to virtually the entire Atlantic seaboard. United States import and export figures for 1814 indicate it was by far the worst year for foreign trade that the nation had ever seen. For Philadelphia merchants, the only other year of comparable devastation was 1793 when yellow fever had closed the port and emptied the city.

One result of the arrival of the British blockading squadron at the mouth of the Delaware Bay in 1813 was that Waln’s wharf at the foot of Spruce Street fell idle. Indeed, for the duration of the war, the docks of Philadelphia were lined with empty ships. Other vessels lay at anchor in the river, while even less fortunate American ships were bottled up in the harbor at Canton, trapped halfway across the world by British patrols. For Robert Waln, all of this meant substantial losses - loss of money tied up in idled ships and empty warehouses, and loss of profit on stagnated capital. Like many American merchants affected by the downturn, Waln transferred his capital away from maritime commerce and into domestic manufacturing. It was within this context that he purchased an interest in the Phoenixville Ironworks in 1812 and soon after set about the business of textile manufacture in Trenton.

Although from a financial standpoint Robert Waln managed to weather the War

of 1812, the troubling times nonetheless took their toll. By 1815, he had

to all intents and purposes retired from the leadership of the merchant firm

he had overseen for so many years. Day-to-day management of most aspects of

his business, including the affairs related to his investments in the Eagle

Factory, were turned over to his second son, Lewis Waln. The elder Robert

Waln continued on in semi-retirement, enduring another financial downturn

in 1819 and serving as a director of the Bank of North America, the Philadelphia

Library Company and the Pennsylvania Hospital, and as a trustee of the University

of Pennsylvania and the Estate of Stephen Girard.

5. The Eagle Factory

A. The Robert Waln and Gideon Wells Years

At the time of his death in 1784, the elder Robert Waln was owner of substantial property in Trenton that was centered on the Trenton Mills, formerly one of the largest colonial gristmills in New Jersey, located at the present-day South Broad Street crossing of the Assunpink Creek (Figure 7). This mill seat and surrounding land, the future site of the Eagle Factory, passed to his daughter, Hannah, wife of Gideon Wells. Over the following half century, Gideon Wells and, more importantly, Hannah’s brother, Robert Waln, Jr., together oversaw and developed the family’s Trenton holdings for manufacturing purposes, eventually, in the mid-1830s, ceding total control of these properties and related businesses to Robert’s son, Lewis Waln (Figure 8).

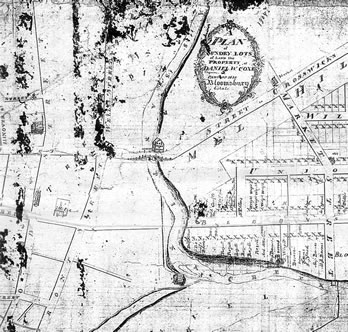

Figure 7. A Plan of Sundry Lots of Land the Property of Daniel W.

Coxe. Circa 1804. Scale 1 inch: 260 feet (approximately). Gideon and Hannah

Wells’ gristmill is shown adjacent to the bridge over the Assunpink

Creek.

From the mid-1780s through into the first decade of the 19th century, the Trenton Mills continued in operation as a grain processing facility and seem to have been mostly the responsibility of Gideon Wells. The business evidently did not fare well. By 1803, Gideon Wells was bankrupt, and in that year his life estate was conveyed to two assignees, Archibald McCall and John Dorsey, who granted the rights to his part of the 29-acre mill tract to Robert Waln. In the same year, Hannah Wells also mortgaged her interest in the mill and other premises to her brother.

By 1814, with the gristmill still struggling and about to be challenged by a brand new mill erected by Daniel W. Coxe on the banks of the Delaware, Robert Waln and Gideon Wells concluded that the same factors that had made the Assunpink property a choice location for a colonial merchant gristmill might be equally advantageous for a modern textile manufacturing plant. It was this realization that led to the founding of the Eagle Factory. Waln, for his part, agreed to provide the capital for constructing buildings and carrying on the business in exchange for a share in its ownership; the more financially constrained Wells would effectively oversee the operation of the factory. Waln’s motivations in getting involved in the establishment of the Eagle Factory were part altruistic and part self-serving. He evidently wished to help out his sister and her husband in a time of financial difficulty and, in a general sense, sought to advance the development of American industry. However, he also wanted to put capital idled by the war back to work and to diversify his commercial interests, thereby making his personal fortune less vulnerable to future disruptions in international trade. Waln and Wells also took the additional step of leasing parts of the mill tract and water power to two other newly founded textile manufacturing enterprises, the Trenton Manufactory of Lawrence Huron & Company and the Trenton Woolen Manufactory, to be located immediately downstream of the Eagle Factory.

In setting up the Eagle Factory, Waln and Wells were cognizant of other similar ventures. Waln, in particular, paid heed to other textile manufacturing ventures in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic states and was in contact with mill owners and merchants in New England and Paterson concerning mill machinery and business practices. The Paterson experience was of no small interest, since mills of similar type were being put into operation around the same time and in reasonable proximity to Trenton, thus potentially vying for a share of the New York/New Jersey market.

In their initial manufacturing efforts Waln and Wells, like most other merchants involving themselves in the textile industry, reasoned that if they focused the Eagle Factory’s production on coarse fabrics and less refined cotton goods they would be better able to compete with British imports. By the summer of 1815, Wells was advertising locally that the factory had for sale “a good assortment of cotton cloth” and was also marketing cotton yarn “warranted equal to any ever manufactured in the United States.” By February of 1817 production had expanded to the point where plaids, checks, bed ticking, shirting, sheeting and stripes were all being sold at the nearby factory store.

However, as the second decade of the 19th century wore on, the price of cotton fluctuated and the market for Trenton textile products proved unstable. In July of 1819, Gideon Wells informed Robert Waln that he was prepared to shut down the mill if the company’s “tickens,” an Eagle Factory bed cloth specialty then selling at “a dreadful price,” were no longer accepted by merchants. Wells put on a braver face for the census taker in the following year, noting that “The Establishment is doing pretty well considering the general depression of the Times, and does not appear to require any additional protection from the …. Government.”

Yet, around this time, and largely because of the difficulty in sustaining the business, a more serious situation was developing behind the scenes, which soon caused the partnership between Robert Waln and Gideon Wells to unravel. Between May and September of 1819 Wells was involved in court proceedings with the Trenton Banking Company concerning his defaulting on a mortgage of $22,000 for his share of the mill property. Waln, from notes in his account book and correspondence in early 1820, appears not to have been aware of this mortgage, and believed he had a prior claim on Wells’ Trenton assets, stemming from the financial arrangements made in setting up the Eagle venture. Finally, in 1819, with the cotton industry still in dire straits, Waln transferred his share of the Eagle Factory and associated property to his trustees. Waln and Wells then advertised the factory property for public sale in early November of that year (Figure 9), with a clear indication being given that any transaction would be subject to the conditions governing Gideon Wells’ life estate. The sale, slated for December 7, 1821, apparently attracted no buyers. In the following year, Robert Waln’s son, Lewis, took over the enterprise, purchasing his father’s interest in the Eagle Factory for $15,000.

Lewis Waln’s involvement with the Eagle Factory dates from at least

1820, and by May of 1821, judging from some specific accounting procedures

he set up with regard to Gideon Wells’ activities, he appears to have

been overseeing much of the mill’s business from Philadelphia, presumably

on behalf of his father. Thus began the period of Lewis Waln’s control

over the Eagle Factory, which extended over almost three decades. Making use

of Lewis Waln’s letter book and correspondence, along with census data,

newspaper advertisements and maps, the following sections of this article

elaborate on various facets of the Eagle Factory – management and labor;

the physical plant; raw materials and products – before summarizing

the subsequent history of its operations from the early 1820s into the early

1840s.

B. Management and Labor

Management of the Eagle Factory was accomplished through a close-knit, three-tiered hierarchy of owners, superintendents and overseers, with family ties often playing an important role in determining who filled positions in the two upper tiers (see above, Figure 8). The owners supplied the capital, hired the senior staff, handled the accounts, made decisions about the purchase of machinery, and set company policy with regard to production. The factory superintendent would have been responsible for making sure that the factory was running efficiently and being operated safely. The superintendent was aided by his subordinate overseers, who supervised the labor force and likely received bonuses when the factory workers exceeded specified production levels.

Ownership in the early years was shared by Robert Waln and his brother-in-law, Gideon Wells. In 1822, Robert Waln’s ownership stake was conveyed to his second son, Lewis, who shared tenurial control of the factory property with the Wells family until 1829, at which point he assumed sole ownership of the Eagle Factory site. The Walns, based in Philadelphia, held the purse strings and effectively had the final say in the factory’s management. Gideon Wells, living in Trenton (probably in the main dwelling on the original mill tract), functioned both as an owner and as the principal on-site manager of the mills’ daily operations up into the mid-1820s, then being succeeded by his sons (Lewis Waln’s cousins), Charles and Lloyd Wells.

Robert Waln initially sought a superintendent with New England mill experience to assist Wells in the day-to-day management of the factory, but had no success finding a suitable candidate. Eventually, a Mr. Longstroth (probably John Longstreth, a member of a prominent local milling family) took the position. By 1821 James Hoy appears to have been serving in a senior management position, either as superintendent or overseer, for in July of that year he was entrusted with the task of going to Philadelphia to select cotton for the Eagle Factory. By January of 1826, however, Hoy had been recently discharged by Lewis Waln, moving soon after to take on a senior post at the neighboring Trenton Cotton Factory, where he eventually ascended to full ownership in 1834.

From the mid-1820s onward, in concert with the gradual exit of his uncle, Gideon Wells, Lewis Waln frequently relied on family members to handle the running of the Eagle Factory, entrusting management tasks at various times to his cousins Charles W. and Lloyd Wells, his brother William, and his nephew William P. Israel. By January of 1826, two of Gideon’s sons, Charles and Lloyd (who later removed to the mill community of Somersworth, New Hampshire) appear to have been supervising the Eagle Factory. By 1827, and continuing up until the fall of 1829, Lewis Waln’s brother, William, and his cousin, Charles W. Wells, were managing the establishment.

In 1831, Lewis Waln was looking beyond the immediate family for management expertise, intending to hire William Hines of Sandy Hill, New York as a new superintendent with the specific charge of directing the machine shop and the factory. Around this same time, Waln was also receiving detailed correspondence from his nephew, Robert Israel, who was then in Lowell surveying the mills there. Robert Israel later removed to Portsmouth where he worked for the Great Falls Manufacturing Company and supplied throstles for the Eagle Factory. In its waning years in the early 1840s, the Eagle Factory was managed by another of Lewis Waln’s nephews, William P. Israel. In 1845, with the factory up for sale, William Israel left Trenton for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he set up a business manufacturing looms.

In many respects, the management structure at the Eagle Factory, with its strong basis in the Waln and Wells families, resembled that of many late 18th- and early 19th-century textile mills in Rhode Island and eastern Massachusetts. In New England mill villages like Slatersville in the Blackstone Valley, the owners/partners engaged in hands-on mill management and knew intimately the milling processes and machines that were involved. Samuel Slater was notoriously distrustful of outsiders and believed strongly that a successful textile manufacturing business would ensue when actively managed by a partner or son. At Slatersville, when a mill manager retired, Slater typically turned to his family rather than a professional agent to find a replacement, averring that successful manufacturers “employed their families …. and, to the extent of this savings of the wages and superintendence and labor, realized the gross profits of manufacture.”

With regard to the mill labor force, in its early years of operation the Eagle Factory probably again followed the Slater model wherein mills frequently employed entire families – husband, wife and children. Under this system, families could express a preference for where their children were employed and sometimes they would all work together. Setting family influence aside, men were assigned the highest paying jobs (as overseers, managers, spinners, watchmen, second hands) and age was often a factor in addition to gender. Overseers were often males in their thirties or forties, while second hands were usually in their twenties. Women typically operated the power looms. Boys and girls, sometimes as young as seven of age and working for minimal pay, performed many of the more degrading and menial tasks that the adults preferred not to carry out, such as picking cotton.

The earliest labor data for the Eagle Factory are given in the federal census of manufactures of 1820, in which Gideon Wells reported employing 120 men, 60 women and 250 children for a total annual wage of $26,000. There is no easy way of assessing the degree of family representation or establishing a full breakdown by gender, although the fact that women and children accounted for 72% of the factory’s labor pool was not unusual for the time, when the nation’s industrial workforce as a whole displayed a similar ratio. In 1833, Lewis Waln reported that the Eagle Factory employed 40 men, 80 boys and an unspecified number of girls, although one suspects the latter figure would have been well in excess of 100. Waln’s reliance on women and children for labor, which bordered on the exploitative, is made plain in a communication to Patrick Jackson, Chairman of the Committee on Cotton, in which he comments that in the United States “the wages of labor are received principally by women & children, whose labor under the circumstances would be of little value so that nearly the whole amo’t of their wages might be considered as gained in an estimate of the National industry.” The Eagle Factory likely employed very few immigrants, since this practice was not widely adopted until the mid-19th century.

Judging from his correspondence in the 1820s, Lewis Waln did not envisage difficulty in finding workers for the Eagle Factory. In early 1823, having reduced his weavers’ wages owing to a decline in the price of hand loom goods, he noted that “altho’ no doubt disagreeable to the weavers [this] ought not to occasion such dissatisfaction as there are hundreds here who would be glad to be in their situation.” By 1825, however, the female component of the factory workforce was evidently in need of bolstering as newspaper advertisements were being run in search of 16 to 20-year old girls (Figure 10). This development may reflect both the laying off of handloom weavers and the factory’s increasing reliance on power looms, two related trends that are evident at the mills in the mid-1820s. It perhaps also hints that the Eagle Factory was consciously adopting facets of the Waltham-Lowell system, shifting away from traditional family labor and looking to hire girls and young single women from surrounding agricultural areas. The fact that the Eagle Factory was situated within an existing population center may have further affected the composition of the labor force, causing fewer families to be hired en bloc.

The progress of textile manufacture in New England was always of acute interest to the Walns and Wellses, and from their original establishment until well into the 1830s the Eagle Factory likely modeled its managerial and labor practices on the exceptionally productive mills in Waltham, Lowell and elsewhere in eastern Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Francis Cabot Lowell, following his successful introduction of power looms at Waltham in 1814, began to develop a predominantly female workforce at mills that he and his fellow entrepreneurs, the “Boston Associates,” operated. This trend found its fullest expression in the mill town of Lowell, beginning in the 1820s, where boarding houses were provided for women who were occupied in the factories up to six days a week. The extent to which Robert Waln, Gideon Wells and Lewis Waln deliberately built up a female workforce is unclear. Likewise, it is not known how and where the millworkers were housed, although the early 19th-century development of the residential neighborhood known as Mill Hill may have been spurred in part by the textile mills on the Assunpink.

That the mills of Lowell were the yardstick by which the Eagle Factory was

measured is apparent from Lewis Waln’s soliciting of information from

his nephew Robert W. Israel in the late summer and fall of 1831. Israel sent

Waln several letters about the production, technology and labor composition

of key mills on the Merrimac River. For example, Israel provided Waln with

a detailed description of each of the departments at the Suffolk Mills, tallying

who was employed in the carding, spinning, dressing and weaving rooms and

also calculating their earnings. The carding room, for instance, employed

two overseers, a card grinder, three people who stripped the cotton, picker

tenders, “cotton boys” who carried the cotton, speeder tenders,

spare hands and others who were used in drawing or lapwinding.

C. Physical Plant

At the peak of its development in the 1820s and 1830s the Eagle Factory comprised at least three separate water-powered industrial buildings, an elaborate hydropower system, a dye house, a sizing house, a drying house, a blacksmith shop and several other smaller ancillary buildings, including a pair of storehouses, an office and the Eagle store, where factory goods were available for sale. The entire complex occupied almost 30 acres and extended across both sides of the Assunpink Creek, upstream and downstream of the Greene Street (present-day South Broad Street) bridge (Figure 11).

The dominant feature of the factory was the large mill building erected in 1814-15 on the south bank of the creek immediately downstream of the Greene Street bridge. No images of this building survive and its footprint appears on only a handful of mid-19th-century maps, but its basic dimensions and essential form are described in several newspaper advertisements and inventories prepared for insurance purposes. In 1824, Lewis Waln, in furnishing information to Ralston & Lyman, prospective insurers, reported that “[t]he factory is of brick, 5 stories high, exclusive of the basement, which is underground, length 54 feet, breadth about 38 feet.” He went on to note that the structure was “substantially built and plastered …. the stairs are carried up in a brick building adjoining which has a cupola and bell …. [and] the waterwheel is on the outside of the factory enclosed partly with brick and partly frame.” The descriptions provided for insurance purposes contain numerous other details about the building, many of which focus on its heating system and fire precautions. Waln was acutely aware of the risk of fire from malfunctioning machinery and the various manufacturing processes being conducted in the building.

Each floor of the Eagle Factory (as the building was usually known) was given over to a specific manufacturing activity. The first and second stories were used for spinning, the third and fourth for carding, while the fifth housed mules for producing the finer and softer yarns used as weft on the loom. The data provided to Ralston & Lyman in 1824 included details of the machinery on each floor: ten throstles (with a total of 960 spindles), two spooling machines and one bobbing machine on the first floor; ten throstles (864 spindles) on the second floor; 26 carding machines, four roping frames and four drawing frames on each of the third and fourth floors; and three mules (679 spindles) on the fifth floor. This arrangement and quantity of machinery appears to change very little between 1820 and 1830. The number of spindles reported in the federal census of manufactures in 1820 was 2,500, while, in 1829, in information supplied to the Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company, the machinery is almost identically reported except that an additional mule (with 269 spindles) had been installed on the fifth floor.

It seems likely that from the outset the main Eagle Factory building was used primarily for carding and spinning, and probably continued in this vein into the early 1840s. There is good reason to suppose that much of the carding and spinning machinery was acquired from New England. As early as October 1815, the firm of Hines, Arnold & Co. of Rhode Island was advertising in the Trenton newspapers that “cotton machinery built of the best of materials, warranted to operate as well as any now in operation” could be found at the “Eagle Cotton Manufactory” and was presumably available for purchase there.

An important process that preceded the carding and spinning of cotton was the picking and cleaning of the fiber, whereby extraneous matter, such as insects, seeds and dirt, was removed. At the Eagle Factory, this task, probably accomplished by running the fiber through water-powered machines with rotating teeth, was carried on in the old gristmill building on the east side of Greene Street. Lewis Waln was always at great pains to emphasize to potential insurers of the factory that this work was conducted in an entirely separate building, since the machinery was a potential fire hazard. The old stone gristmill was also used for dressing the cotton fiber, which entailed its immersion in vats, and part of the building served as a machine shop for the mills in the 1820s. Toward the end of the factory’s life in the 1840s, parts of the gristmill building were separately rented out to non-textile-related businesses.

A third water-powered industrial building within the Eagle Factory complex was the weaving mill, also referred to as the power loom building, situated on the north bank of the Assunpink on the east side of Greene Street. This structure was probably not erected as part of the original construction in 1814-15, since no clear reference to the presence of power looms at the factory has been found prior to 1821. The development of power loom machinery in the United States was still in its infancy in 1814 and it is reasonable to assume that the only machinery on the Eagle site at the outset was involved in the picking, cleaning, carding, spinning and warping processes. Weaving was likely undertaken by a bevy of women and girls, and perhaps a few men, using handlooms, some of this equipment being on the mill premises (in unused space in the main factory building and the old gristmill), but much of it probably distributed around the Trenton area in local homes.

The Eagle Factory’s transition from hand to power loom weaving is one of the most interesting aspects of the mills’ history, and appears to have occurred progressively over the course of the 1820s. The first unequivocal indication of power looms being used at the site occurs in late 1821. The sale advertisement prepared in November of that year by Robert Waln and Gideon Wells notes “a stone factory, containing thirty power looms, with the necessary machinery for weaving cotton goods” (see above, Figure 9), while in the following month, Lewis Waln reports obtaining insurance coverage to the tune of $5,000 on “the building and machinery in the Weaving Establishment.” No mention of power looms is made in either the federal census of manufactures in 1820, nor in an inventory of mill machinery owned by Gideon Wells, compiled in September of 1819 in connection with court actions taken against him over his defaulting on his mortgage payments for his share of the Eagle property. However, it may be relevant that Hannah Wells (Gideon’s wife, who retained ownership of the land east and upstream of the Greene Street bridge) purchased water rights to raise the level of the water in the millpond in April of 1819. This possibly implies an upcoming modification of the Eagle Factory hydropower system to allow for construction of a weaving mill on the north bank of the Assunpink on the east side of Greene Street.

Subsequent documents and historic maps make clear that a weaving mill was located on the north bank of the creek across from the old stone gristmill. Information supplied by Lewis Waln to Ralston & Lyman in May of 1824 states that the “power loom building is of stone with the exception of the gable ends which are of wood or frame, it is three stories high about 60 feet front on Greene Street in Trenton and 22 feet deep. Stands directly on the Assanpink on the northerly side …. The power loom building with water wheel running gears including drums and shafts is valued at $3,500 … 30 looms with apparatus @ $30 each.”

Throughout the early 1820s, Lewis Waln in his correspondence makes occasional references to the high labor cost and un-profitability of handloom weaving, while also noting that he was pursuing the purchase of additional weaving machinery. In July of 1825, there is a note from Waln discussing various ongoing cost-cutting measures at the factory, along with a reference that “the hand looms hav[e] been stopped.” By January of 1827, based on a report by William Waln to his brother Lewis, there appear to have been two separate weaving facilities: the “old shop” (probably the mill described above), which contained 30 power looms and seven additional Jenks looms; and the “new shop,” with 33 power looms. The location of the new weaving shop is uncertain, but descriptions of flood damage in 1843 imply that it lay on the west side of Greene Street, on the south bank of the Assunpink, between the five-story brick factory and the converted gristmill. William Waln also notes that 34 handlooms were also in use for weaving cottonade and ¾ muslin, demonstrating that the traditional weaving craft still had a place, albeit somewhat reduced, in the factory system.

Throughout the 1830s and into the early 1840s, there are sporadic references to the mill buildings and mill machinery in Lewis Waln’s letter book and related correspondence, but the Waln family’s interest in the physical plant of the Eagle Factory seems to lessen in intensity during this period. In his efforts at hiring William Hines as a superintendent in 1831, Lewis Waln noted that part of the machinery is old and implies that much of the superintendent’s time would need to be spent in the machine shop. The factory ordered a pair of new throstles and a speeder in 1836, and several repairs and investments in new equipment were made following flood damage in 1843, but one’s impression of the factory is hardly one of a place imbued with industrial vigor. Indeed, in July 1843, William P. Israel, proposed moving the 15 remaining looms from the obsolete “old weaving mill” into the upper carding room in the main factory, an act that suggests retrenchment rather than expansion. The waning of manufacturing activity at the Eagle Factory was partly a result of national economic conditions and the overwhelming dominance of New England mills in the textile sector, but was probably also partly due to increasing local competition attendant on the completion of the Trenton Delaware Falls Company’s power canal in 1834-35.

The water power source for the three main industrial buildings – the five-story, brick spinning and carding mill; the converted stone gristmill used for picking and cleaning cotton; and the “old” weaving mill erected circa 1820 - was a large millpond retained by a dam across the Assunpink Creek roughly 50 to 100 feet upstream of the Greene Street bridge. The oldest of these buildings, the converted gristmill (see above, Figure 7), dated from at least the mid-18th century and occupied the site of Mahlon Stacy’s gristmill, erected in 1679. The wheel pit of this mill is believed to have been located in the northern end of the building and in the early 19th century probably contained an undershot or breast wheel fed by a short headrace leading from the millpond. The five-story brick factory, just downstream, was fed by a raceway that passed along the south side of the converted gristmill, under Greene Street, and then emptied water on to what was probably a breast wheel at the eastern end of the building. This same raceway evidently supplied water power to one and possibly two other mills immediately downstream of the brick factory (the Trenton Manufactory, and perhaps also the Woollen Manufactory of Trenton) in the years before the Trenton Delaware Falls Company’s power canal was built; it may also have fed the “new” weaving mill, which is thought to have stood between the brick factory and the gristmill. The “old” weaving mill, on the north bank of the Assunpink, lay directly across the creek from the gristmill, and was powered by a short headrace that drew water form the millpond at the northern end of the milldam.

The Lower Assunpink was beset by several serious floods in the 18th and 19th centuries, a circumstance that was likely exacerbated by the reconfiguration of the creek for water power usage. Most of the mills, and the Greene Street bridge in particular, suffered damage at one time or another, and the facilities of the Eagle Factory were no exception. The converted gristmill was partially destroyed by a flood in February of 1822, which carried away machinery and equipment used in the picking and dressing of cotton. This flood may also have damaged the “old” weaving mill, since Gideon Wells in a letter to Robert Waln in October of that year, notes that “we have been 2 weeks putting in a new water wheel in the power loom factory.”

Another spring freshet in March of 1843 caused equally severe or worse damage. Floodwaters blew out the dam and “an old trunk, unused for years, running from the creek on the east side of the stone factory” (possibly the original raceway to the brick factory [apparently replaced by this time]), carried off “the greater part of the weaving mill on the land side” (apparently the “new” weaving mill), and undermined the Eagle store. The southeastern part of the “stone mill” (the converted gristmill) also collapsed. Repairs followed - the dam was fixed and the raceway was rebuilt - but in the midst of a drought in the following July the waterwheel shaft in the main factory building broke, apparently the result of poor maintenance and old age. It was another month before the wheel was replaced and the factory was fully operational again.

Aside from the various mill buildings and the factory-wide hydropower system,

there were several other buildings on the site. The notice of sale issued

by Robert Waln and Gideon Wells in November 1821 notes a frame dye house,

sizing house, drying house and blacksmith’s shop, a two-story stone

dwelling house with an adjoining two story frame building, and “two

storehouses – one of stone and the other of brick” (see above,

Figure 9). Lewis Waln, in providing information to Ralston & Lyman in

1824, notes “a one story frame dye house … and on the back of

the dye house, a stone building adjoining (used for boiling yarn) one story

high, both of these buildings … partly in the creek,” a one-and-a-half

story frame sizing house, a two-story frame drying house and a shed. These

structures all appear to have been situated on the south bank of the creek

to the west of Greene Street, which is also the most likely spot for the blacksmith’s

shop. Across the creek, again on the west side of Greene Street, were a one-story

frame building, formerly used as an office, and a stone and brick dwelling

with several outbuildings. As indicated by the descriptions of the flood damage

in 1843, the Eagle store was located on the east side of Greene Street, south

of the converted gristmill, probably adjoining the south side of the raceway

leading to the main five-story brick factory building. The store may have

occupied the same two buildings as the pair of storehouses mentioned in the

notice of sale in 1821.

D. Raw Materials and Products

The Eagle Factory appears to have processed between 100,000 and 200,000 pounds of cotton annually, although there is very little consistent quantitative information on the volume of raw material being consumed. In the 1820 federal census of manufactures, Gideon Wells reported that the factory took in 120,000 pounds of cotton valued at $24,000. Similar data compiled by the Secretary of the Treasury in 1833 showed the Eagle Factory annually processing some 170,000 pounds of cotton valued at only $18,700, a clear indication of the declining cost of the raw material.

The archival record is similarly reticent concerning the source of the cotton used at the Eagle Factory. In the early years of its operation, with the Waln family actively engaged in merchant activity with the Far East, a portion of the cotton fiber being processed in Trenton seems to have been imported from China and the Bengal area of northeast India. However, as cotton growing expanded in the southern States and domestic manufacturing responded to protective tariffs on imported goods, the primary source of Eagle Factory cotton soon became the planters of the Carolinas, Georgia, Louisiana and the Tennessee Valley. Lewis Waln, in his business correspondence, periodically refers to shipments of cotton bales arriving at his wharves in Philadelphia, sometimes noting it as deriving from Louisiana, Carolina or Upland (the more elevated interior regions of the southern States). Upon the cotton’s arrival, Waln would notify agents of the Eagle Factory to come and select fiber for processing at their mills.

Over the years, a wide range of cotton goods was manufactured at the Eagle Factory, although as with raw materials being used, it is difficult to quantify the production. In 1820, Gideon Wells informed the census enumerators that “the quantities of Cotton Cloth manufactured during the year will not fall short of 480,000 yards.” This was almost certainly an overly optimistic projection, as Lewis Waln in 1833 reported the annual production at 100,000 yards from 40% more raw material.

During the first decade or so operation, the production emphasis appears to have been on yarns and hand-woven goods, but from around 1820 onward machine-made fabrics increasingly dominated. Coarse cotton cloth for sale in the domestic market was the principal output and this was fashioned into a variety of fabrics in different widths and weaves. Among the more common types of cloth made at the Eagle Factory were plaids, checks, muslin, gingham, ticking or bed ticking, sheeting, shirting, chambray, twill, linsey and some distinctive products such as “Wilmington stripes,” “Assunpink ticks” and certain types of shawls (Figure 12). Ensuring the integrity of Eagle products in the marketplace was of some concern, and in 1820 Lewis Waln engaged a Mr. Thomas to design a label with “the words ‘Eagle Factory’ printed with a French type which he thinks will be less liable to be counterfeited than handwriting.” The Eagle Factory has also been suggested as a possible source of the so-called “Trenton tape,” a characteristic binding found on many early 19th-century quilts made in the Delaware Valley.

An especially revealing glimpse of the Eagle Factory production is provided in a letter of January 16, 1827, in which William Waln reports back to his elder brother, Lewis, on the mills’ output. At that time, 25 of the 37 power looms in the old weaving mill were turning out “jacks” or jaconet, a thin cotton fabric between cambric and muslin, used for dresses and neck-cloths, at the rate of 26.5 yards per loom per day. Nine of the remaining 12 looms were making ticking (cloth used for covering beds), while the final three were given over to flannel, muslin and drilling, all of these producing at the rate of between 13 and 18 yards per loom per day. In the new weaving mill, all 33 power looms were making ticking at a rate of no more than 15 yards per loom per day. Twenty-four of the 34 handlooms still in use at the factory were producing cottonade, a thick, stout cotton fabric; the remaining ten were making ¾ muslin. Over the winter of 1826-27, clearly the factory was focused on producing jaconet, ticking and cottonade.

Eagle Factory products were marketed extensively in the Delaware Valley and Middle Atlantic region, but also saw some distribution further afield, not only in the United States, but also overseas. At the site itself, the Eagle store, conveniently located on Greene Street between the mills and the True American Inn, served as a valuable outlet. Numerous advertisements appeared in the Trenton newspapers in the second and third decades of the 19th century offering cotton goods for sale at the factory store. No less important were the Waln & Leaming store and other commission houses in Philadelphia, where Eagle goods were periodically sold or auctioned. During the depression years of the late 1830s and early 1840s, in an effort to facilitate trade, the factory issued scrip notes to valued customers as an alternative to hard currency (Figure 13). This mode of exchange was likely acceptable at the Eagle store in Trenton, and perhaps also at Waln & Leaming’s in Philadelphia.

The Waln family’s connections with merchants and cotton planters in

the southern States also appear to have led to some distribution of Eagle

factory products in these more distant parts. Lewis Waln noted in 1822 that

“in a conversation with some Alabama merchants this morning, they said

that a stout coarse cotton article for their slaves was very much wanted,

something 4/4 wide and of the stoutness of the Linseys made in Trenton ….

No. 4 or 5 closely woven I suppose would suit.” While the South may

have been a logical outlet for Eagle Factory goods, there is no evidence in

Lewis Waln’s letter book that markets were sought further north in New

England, or even in New York; presumably the mills of Lowell and other textile

centers adequately catered to the clothing needs of this region. Domestic

sales fluctuated tremendously, however, as the price of coarse cottons fell

and tariffs only partially protected manufacturers. To help offset this uncertainty

and keep stocks of unsold cloth at a minimum, the Walns developed an important

overseas market for Eagle Factory goods in South America.

E. The Lewis Waln Years

The later years of the Eagle Factory operations, from the early 1820s through into the mid-1840s, were dominated by Lewis Waln and saw the mills’ continued mixed profitability, followed by their eventual demise. Waln’s letter book and miscellaneous related correspondence vividly document the affairs of the factory during this period, particularly in the 1820s and 1840s. This material, much of it involving Waln’s Eagle Factory interactions with his uncle Gideon Wells, his cousins Charles W. and Lloyd Wells, his brother William, and his nephews William P. and Robert W. Israel, deals mostly with financial, insurance and managerial issues. It is important to note, however, that Waln’s principal business commitments during this time centered on his role as a partner in the Philadelphia merchant firm of Waln & Leaming. Although eventually gaining total control of the Eagle Factory, he initially chose to keep the business of the mills somewhat at arms length, acting chiefly as a commission merchant, and even going so far as to request in 1822 that the Waln name be omitted from newspaper advertisements for Eagle goods.