The Kelsey Building, 1911

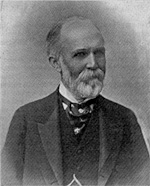

Henry

Cooper Kelsey was a self-made Victorian gentleman, the great-grandson of a

Scots tanner and currier, who was an early resident of Newton, Sussex

County. In 1858, when the young Kelsey

was 21, he took over a Newton store and became active in Democratic

politics. He was appointed postmaster

the next year, serving until the Republicans came into power nationally in

1861. He bought the New Jersey Herald

that summer and settled into journalism and politics. Kelsey, who had married Prudence Townsend the

year he became a publisher, was appointed a judge of the Court of Common Pleas

in 1868, filling the vacancy caused by her father’s resignation. In July of 1870, the governor appointed him

secretary of state.

Henry Cooper Kelsey

He

stayed in the job for 27 years and remained in Trenton for the rest of his

life. Together with Benjamin F. Lee,

clerk of the N.J. Supreme Court for 30 years, and Henry S. Little, clerk of the

Chancery Court, he ran state Democratic politics for three decades ~ choosing

the party candidates for governor and U.S. Senate and a host of lesser offices,

and writing the party platforms. The

Secretary of State, a contemporary wrote, “was a man of the most precise

habits. If you were two minutes late on an appointment with him, he was apt to

close the door in your face.”

From

the time he entered state government until his death 50 years later, he lived

in a suite of rooms at the Trenton House, a hotel on North Warren Street.

Beginning in 1872, when his doctor advised him to go to Europe for his health,

he and Mrs. Kelsey sailed each spring for Europe, returning in the fall.

The

Kelseys had been married for 43 years when she became ill, was hospitalized and

died in 1904. Following his wife’s

death, the childless widower resigned from all social activities. He made large gifts to her church and the

hospital where she died but wanted a more substantial memorial. Although he had no previous connection with

the School of Industrial Arts, which provided night classes to factory workers,

he decided to donate a building to the school, which used rented rooms. Having determined on his gift, he quietly

acquired the land for $19,000, then set about hiring the best architect he

could find.

If Cass Gilbert wasn’t America’s most famous architect when Kelsey made the announcement of his intentions on May 2, 1909, he hadn’t long to wait. He had been Stanford White’s personal assistant at McKim, Mead & White. In 1905, he won the competition to design the New York Customs House and he was hired four years later to work on the Woolworth Building. The 66-story skyscraper was the tallest building in the world when completed in 1913, and remained so for another 20 years. Conspicuous for the beauty of its perpendicular Gothic style, it remains one of Manhattan’s most famous buildings and the cornerstone of Cass Gilbert’s reputation.

Kelsey

met with the architect, saw his gift announced and sailed for Europe, as was

his habit. Gilbert would later explain

that the princely nature of Kelsey’s gift had made him think of princely art

patrons of the Renaissance. He modelled

Mr. Kelsey’s building on the great Florentine Palazzo Strozzi, built in 1489.

The

whole project was intended to memorialize Prudence Townsend Kelsey: A bronze

tablet on the building’s facade is dedicated to her and the first-floor

auditorium was named Prudence Hall. But

her widower also lavished more than $12,000 on the decoration of a single room

on the second floor, a permanent exhibit space for the pieces his wife had

collected on their annual trips to Europe.

Under the pediment of Siena marble and through the double doors ~ the

outer mahogany, the inner satinwood ~ is the second-floor room inscribed: “In

Memoriam Prudence Townsend Kelsey.”

Henry C. Kelsey himself arranged its contents, as a permanent reflection

of the wife he never ceased to mourn.

The extent of his feelings can be gauged by his opening remarks at the

Kelsey Building’s dedication ceremonies:

“When,

on that bitter winter night, now more than seven years ago, the light of my

life went out, all the world seemed dark and cold to me. My heart was chilled, my reason staggered and

I felt that for me the end could not come too soon. But after a period of despair I was aroused

to realize that my own work was not yet done ~ that there were new duties

calling me ~ duty to the community, duty to my friends and hers, and, above

all, the glad duty to honor and exalt her memory in every possible way, for to

her all that I was or had been or am ~ my very existence at my mature age ~ was

due.”

His

Victorian excess of feeling is mirrored in the room, where porcelain cherubs

perch atop framed portraits of the Kelseys; six clocks are stopped at 11:49;

and a number of small calendars are turned permanently to Sunday, January 3,

the time and date of her death in 1904.

Small pictures of Mrs. Kelsey are scattered among the cabinets holding

her belongings, and one shelf displays a sachet envelope, with her calling card

attached. On it is written: “This little

sachet was the last thing I took to Blessed Prude ~ a day or two before

Christmas 1903 (at the hospital). God Bless her soul. O! My darling, darling wife.”

Outside the room, suspended from the building’s facade by lacy ironwork, is a large clock. A great proponent of public clocks (and a man renowned for his own promptitude and his expectation of it in others), Kelsey had two bronze markers attached to the west clock face, permanently recalling his wife’s death at 11:49.